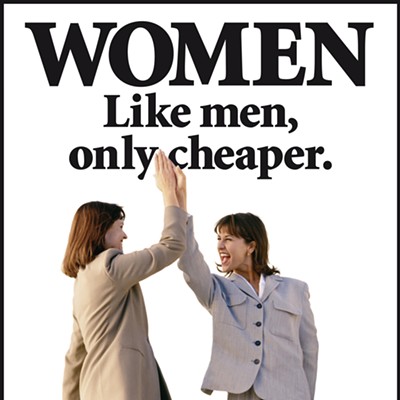

While most people think of April 14 as the 11th hour of income tax preparation, for half the population it has a different kind of economic significance. It's the point in the year—combined with the previous 12 months—at which women will have finally earned as much as men did in the previous calendar year. Dubbed Equal Pay Day, it is a stark reminder that even in 2015, women still don't earn the same paycheck as their male colleagues.

Despite the fact that gender-based pay disparities have been illegal since the passage of the Equal Pay Act in 1963, women make about 80 cents for every dollar paid to a man doing the same work in Oregon. The gap has narrowed, but it remains and grows larger as women age, according to a recent analysis by Fortune.

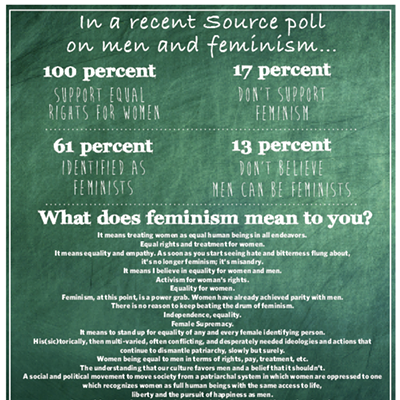

Some fields are more equal than others. Bureau of Labor Statistics data shows that female media producers, despite being a minority in their field, actually make more than their male colleagues. Counselors and biological scientists are both near parity. But when it comes to personal financial advisors, physicians, and surgeons, women make less than 65 percent what men do.

"In the political realm, when I was there, I had pay equality," says former Bend City Councilor Jodie Barram. "The men who sat alongside me got paid $200 a month, just like me," she quips.

Certainly pay equity in government work seems expected, given established salary structures and the ability of public records law to expose inconsistencies. But in the private sector, these systems may not be in place. The result: Even in jobs traditionally held by women, men earn more for their work.

According to a study published in the March issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association, male nurses make considerably more than female ones. While the average gap was $5,100 per year, some nursing specialties saw even more dramatic disparities. For instance, the study found that male nurse anesthetists make on average $17,290 more annually than their female counterparts.

So why aren't wages closer to equal across the board? There are a number of theories, but no consensus. Researchers have honed in on some "explained" factors: things like fewer educational opportunities and less workforce experience. Still, even after accounting for these influences, a gap remains.

Economist Claudia Goldin writes in the April 2014 issue of American Economic Review that there are a few reasons this could be happening.

"Some would claim that earnings differences for the same position are due to actual discrimination. To others it is due to women's lower ability to bargain and their lesser desire to compete," Goldin writes. "Still others blame it on differential employer promotion standards due to gender differences in the probability of leaving."

In her view, the biggest contributor to unequal pay is a system that rewards workaholics and penalizes those who need or desire greater flexibility with regard to where and when they work.

"[The solution] must involve alterations in the labor market, in particular changing how jobs are structured and remunerated to enhance temporal flexibility," Goldin writes. "The gender gap in pay would be considerably reduced and might even vanish if firms did not have an incentive to disproportionately reward individuals who worked long hours and who worked particular hours."

Women, who are disproportionately responsible for caring for children and other family members, are more likely to benefit from this kind of flexibility. It could also increase the number of women in leadership positions.

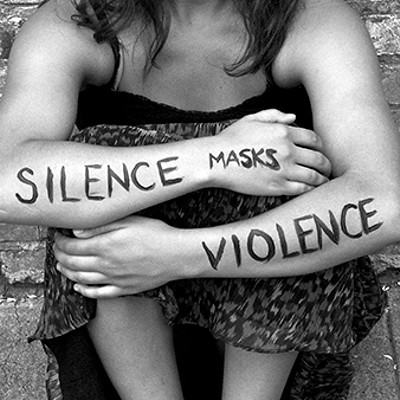

"I think about how organizations—nonprofits, NGOs—that invest in indigenous cultures and focus on following the research are saying, 'Hey look, if we raise up the status of women in these populations, the whole population does better,'" explains Janet Huerta, executive director of Saving Grace. "And yet, we're not applying that here."

What would such a world look like? Childcare would be subsidized, she says, and mothers would have the resources to make decisions about their work-life balance and whether or not to work outside the home.

"A lot of times it's not a choice," Huerta says. "It's a luxury to be able to feel like there's enough money coming in that you can stay home with the kids. Or that dad is going to be a stay at home dad."