The good news is they didn't go up," says Angus Duncan, speaking about greenhouse gas emissions. He adds, "The bad news is they don't go down."

For the past 40 years, Duncan has been working with local and national agencies to modify energy policy, and for the past eight years has chaired the Oregon Global Warming Commission, a group that makes recommendations to Oregon State Legislature and to various governmental agencies on how to reduce carbon emissions.

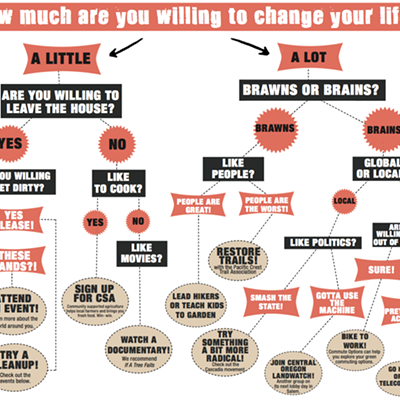

This commission is the closest thing that governmental agencies in Oregon have to a consciousness about global warming—and, as such, provides suggestions for correcting behaviors, like creating better transit systems so residents can drive less, and eliminating coal-based energy sources. But, much like New Year's resolutions, suggestions by the commission are merely recommendations—and, after several years, that lack of accountability is showing its shortcomings in Oregon's failure to make any real headway toward driving down carbon emissions enough and fast enough to avoid dramatic climate changes.

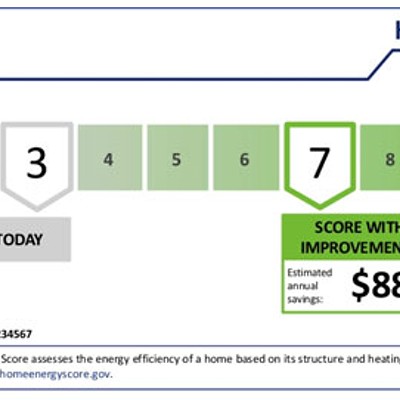

Most broadly, the commission has set three goals, the first of which was to stop the increase of carbon emissions, the primary contributor to global warming. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s in Oregon, carbon emissions were steadily increasingly by one or two percent annually. By 1999, though, Oregon residents and governmental agencies did manage to stop those increases in their tracks.

It is an important date to note for two reasons: For starters, 1999 is a time before An Inconvenient Truth was released, before the Prius was available in the United States and wind generated power was eight percent of current capacity; and second, while Oregon's carbon emissions peaked in 1999, most other states did not manage to curb increases until nearly a decade later.

But the commission has not been satisfied simply by stopping the increase in carbon emissions; to avoid global warming disasters, they understand that carbon emissions actually need to be dramatically reduced. Set in 2010, the second goal for the commission is to reduce carbon emissions in the state by 2020 to 10 percent less than 1990 levels.

"The goal is to start bending (carbon emissions) back downhill," explains Duncan. It is a critical goal—in part because there has been more than enough time for residents to modify their habits, like single-occupancy car commuting and switching from coal-based energy supplies, together which account for roughly half of carbon emissions. Yet, halfway between 2010, when the goal was set, and 2020, the due date, there is no evidence that Oregon is doing anything better than holding the line, nor is it making any motions toward reaching the ultimate goal—reduction of carbon emissions by 2050 to 75 percent of 1990 levels.

In a report card to the state legislature in 2013, the commission essentially gave Oregon a C-plus. "Which," says Duncan, "is not nearly enough," adding, "and we're one of the better states."

Duncan does point out that there have been important lifestyle and public policy changes over the past decade, like maintaining strong Urban Growth Boundaries and improvements in transit systems—both which help reduce the need for and frequency of driving.

But those achievements are not statewide, and topics like Urban Growth Boundaries and mass transit systems remain hotly disputed and slow to take root in Central Oregon. Moreover, there are few indicators that the general population in Central Oregon is taking global warming—and changing personal habits accordingly—seriously.

In Central Oregon, according to interviews conducted by Fuse Insight Labs in 2011 fon behalf of the commission, general attitudes toward global warming remain divided—especially along regional and political lines. In the Bend area, there was a near equal split in respondents between those who "care deeply" and those "skeptical" about global warming. Outside the immediate area, in Redmond and La Pine, the responses were almost exclusively skeptical—a stubbornness that most likely translates to an inability to make change.

It is probably not only too little and too late, but instead the central question about global warming is increasingly how will we adapt to an increasingly dry region that will have more forest fires, less snow for skiing, and less water available for home use, as well as for popular industries like golf and beer.