The rugged expanses of the American West have long supported local economies through rural industries such as cattle grazing, logging, mining and other energy ventures. But recent research suggests that these wild lands may be more profitable in their natural state than tapped for the consumable resources they can provide.

That's good news for advocates like the Oregon Natural Desert Association, which is using the 50th anniversary of the Wilderness Act to raise awareness about the unprotected wild desert lands of central and eastern Oregon and pushing for federal protections.

The Wilderness Act, signed by President Lyndon B. Johnson on Sept. 3, 1964, provides a mechanism for protecting wilderness areas "for the permanent good of the whole people." After signing the act, which was eight years and 60 drafts in the making, President Johnson remarked: "If future generations are to remember us with gratitude rather than contempt, we must leave them a glimpse of the world as it was in the beginning, not just after we got through with it."

A noble goal in and of itself, and one that studies increasingly show is for the economic—not just existential—good of the people.

According to "Protected Lands and Economics: A Summary of Research and Careful Analysis on the Economic Impact of Protected Federal Lands," a report published by Headwaters Economic this summer, western counties that have permanent protections on federal lands—such as National Parks, Monuments, or Wilderness Areas—show higher than average rates of job growth and have higher levels of per capita income.

"Protected federal public lands in the West, including lands in non-metro counties, can be an important economic asset that extends beyond tourism and recreation to attract people and businesses," the report states.

It's easy to see why. In a place like Bend, beautiful natural spaces not only support the tourism and outdoor recreation industries, they also encourage retirees, entrepreneurs, telecommuters and others with the freedom to choose where they live and work, to choose Bend.

"Increasingly the value of protected public land is linked to recreational opportunities as well as the natural amenities and scenic backgrounds they provide which stimulate 'amenity migration,' drawing entrepreneurs and attracting a skilled workforce across a range of industries," the report continues.

And that benefit is dramatic. From 1970 to 2010, western non-metro counties in which more than 30 percent of the county's land was federally protected saw a 345 percent increase in jobs. Otherwise-similar counties without federally protected lands saw just an 83 percent increase. Headwaters Economics discovered a similar trend with regard to per capita income, with each 10,000 acres of protected public land contributing to an increase of $436 in per capita income. In Deschutes County, 76 percent of the land is owned and managed by the federal government, through the U.S. Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management.

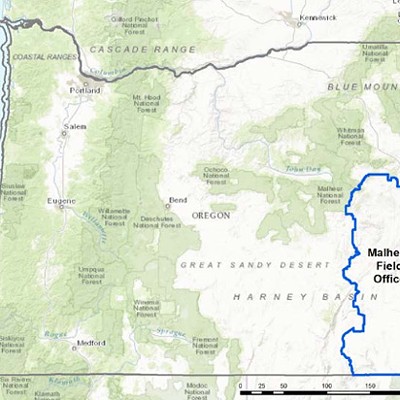

Despite these perks, ONDA Executive Director Brent Fenty says Oregon is suffering from a "wilderness deficit." While Oregon's neighbors have seen a steady increase in federally protected wilderness, Oregon is holding nearly level at about 4 percent. By comparison, Idaho is 9 percent wilderness, Washington is 10 and California is 15. And the protected wilderness Oregon does have is largely on the west side of the Cascades.

"Oregon has gotten caught in this moss curtain," Fenty says. "We barely scratch the surface in Oregon's high desert, despite the fact that it constitutes almost half of the state's land mass."

While nearly 7 percent of Oregon's forests are designated as wilderness, just 0.3 percent of its deserts enjoy that protection. On this side of the mountains, most of the protected wilderness areas are around rivers and mountains, with relatively few encompassing desert areas.

Fenty says that this may be due, in part, to the fact that the sprawling, arid scenes are not postcard picturesque in the same way as a snow-capped mountain surrounded by lush forests. Mostly, though, it's a lack of awareness about these spaces—which Fenty describes as dramatically beautiful in a way that is reminiscent of the American Southwest—and a lack of congressional action.

Wilderness can only be created through an act of the Congress, and there has been little movement on that front. Though Oregon senators Jeff Merkley and Ron Wyden introduced the Oregon Treasures Act and the Devil's Staircase Wilderness Act in 2013, the bills have stalled, and are waiting on votes from the senate and house, respectively.

"These lands can't speak for themselves," Fenty points out. "They need people who care about them and are passionate about them to give them voice."

In the meantime, ONDA is hoping to raise awareness about the high desert's unprotected wild lands through its biannual Desert Conference Sept. 18-20, which incorporates speakers, panels and field trips, as well as other events as part of Wilderness Weekend. The conference will feature keynote speakers including Roderick Nash, author of "Wilderness and the American Mind," Clinton-era solicitor general for the U.S. Department of the Interior, John Leshy, and locals Nature of Words founder Ellen Waterston and author Jarold Ramsey.

As part of the weekend's festivities, ONDA will host a free block party Sept. 20 featuring local bands Truck Stop Gravy, Pitchfolk Revolution and, of course, Wilderness, as well as food, drinks and activities, all in the lot adjacent to Strictly Organic in the Upper Old Mill District.