The World Health Assembly, the governing body of the World Health Organization, has designated 2020 as the Year of the Nurse and the Midwife, in hopes of advancing nurses' and midwives' position in health care.

Giving birth to a child in the U.S. is expensive. Even with insurance, hospital delivery alone averages $4,500 in out-of-pocket expenses, according to The Atlantic. But home births attended by midwives could save money for both the health care system and for families if they were more widely supported, according to a study published last month and co-authored by Missy Cheyney, associate professor at Oregon State University.

Home births also offer families the opportunity to give birth in a familiar atmosphere and at a natural pace.

"I have some clients that come to me and tell me that they had a horrible experience at the hospital; that they felt rushed, and that they could have avoided a crazy outcome like a cesarean if they had just stayed at home and been left alone [to give birth at their own pace]," said Allegra Lilly, one of six licensed home birth midwives in Central Oregon. "Some births take two days, but hospitals may get crowded... A lot of labors get artificially pushed along with inductions that could lead to cesareans."

One out of three mothers gives birth via a cesarean section in the U.S. Women who begin their childbirth process at home or in a birthing center usually have only a 5-7% chance of a cesarean, Cheyney wrote.

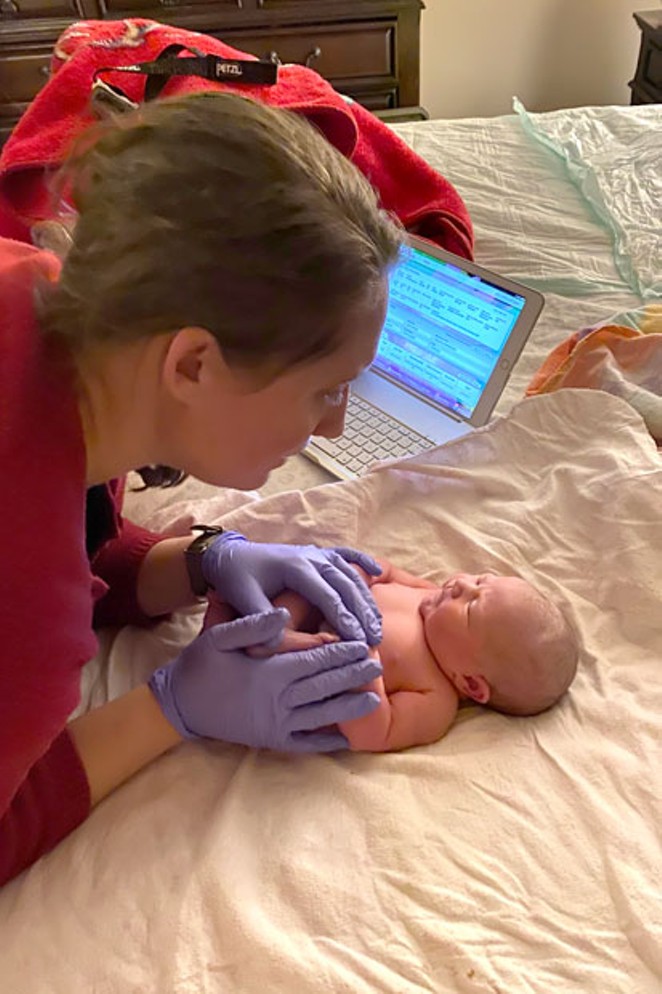

But not all mothers are appropriate candidates for home births and midwives carefully screen their clients throughout the prenatal, postpartum and newborn care periods for risk factors requiring hospitalization. Oregon State law prevents mothers with certain illnesses from accessing midwifery care, such as people with liver disease, substance abuse disorder (with negative effects) and mothers who have pregnancies that last more than a few weeks past the due date.

Home births or "community births" attended by trained midwives are more common in Oregon than other states: Oregon ranks third highest in the nation for density of midwives and midwife-attended births per capita, according to an article published by Plos One in the National Institutes of Health data base.

Midwifery is one of the oldest female professions, documented in the "Ebers Papyrus" from Egypt in 1900 B.C. Today, midwifery is much more common outside of the U.S. According to Cheyney, a majority of pregnancies in peer nations are attended by a midwife. Meanwhile, 98.4% of U.S. births occur in hospitals, with 0.5% of births in birthing centers and 1% at home. Only 11% of births are attended by midwives. St. Charles Medical Center in Bend employs five certified nurse midwives. Patients on the Oregon Health Plan can work with one of them if they choose, according to Lisa Goodman, public information officer for St. Charles.

The U.S. spends more on maternity care than any other county in the world—approximately $110 billion every year—yet is has the worst outcomes among peer countries for both mothers and newborns, according to Cheyney's study.

Despite the lower cost of home births, access to midwives or a natural birthing center is limited because insurance companies do not fully support it. Insurance companies such as PacificSource list midwifery as "alternative care." This conventional perspective sees the birthing process as dangerous, requiring hospitalization. Some private insurance companies provide "out-of-network" coverage for licensed midwives that cover an average of 30-40% of the cost, according to Lilly, who manages her own business.

Bend Birth Center, for example, lists the costs of prenatal care, labor, delivery and six weeks of postpartum care for the mother and baby at $5,000. If a family wants to give birth at the center, it charges $2,600 for the mother and $1,200 for the baby for each 12-hour period they're there.

Lilly explained that it's difficult to get reimbursed through OHP, so most local midwives choose not to accept it. But Lilly does offer discounts to mothers with OHP and has an economically diverse client base.

"I have some clients that are socioeconomically depressed and can barely pay me. Others live in mansions in Bend," Lilly said.

Some mothers may worry that midwives attending home births might not be equipped to deal with life or death situations. Statistics from Oregon in 2012 show the death rate for babies in planned home births was seven times that of births in the hospital.

St. Charles Medical Center provides a hybrid situation at the Bend Family Birthing Center, with a homey atmosphere, Jacuzzi tubs and a "soothing and joyful environment," with a range of medical professionals (including midwives) and life-saving equipment at arm's length, according to its website.

But all the midwives practicing in Central Oregon, including Lilly, have a level of expertise between an OB-GYN and a nurse. They travel to home births equipped with hospital equipment ranging from IV fluids and oxygen to anti-hemorrhagic medication and antibiotics.

Lilly said her "transport rate," where she must take her clients to the hospital, is under 2%.

Cheyney argues that it is imperative that the U.S. make midwives, birthing centers and home births more accessible in all communities. This will help to lower health care costs, increase access to care in underserved communities, reduce complications from unnecessary interventions (like cesareans) and provide an experience that is better matched to some families' needs.

"Community births may also have the potential to provide respectful care that is more flexible and attuned to cultural and personal values, especially when pregnant people are matched with a midwife who comes from their own community and speaks their language," Cheyney wrote in an email to the Source.

"We should not separate the outcomes of care from the experience of care," Cheyney wrote. "How we treat mothers matters as much as the clinical outcome, and we have lost track of that in some places."