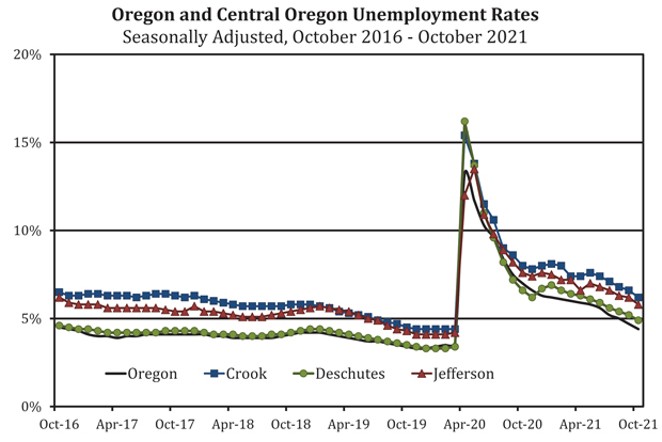

The number of working Central Oregonians exceeds pre-pandemic levels from October 2019 by about 630 jobs, signaling that the economy largely recovered from the shock of COVID.

The Oregon Employment Department reported Nov. 23 that the unemployment rate is around 4.9% in Deschutes County, one-and-a-half points higher than pre-pandemic rates from February 2020, but lower than the 6.9% 10-year average in Deschutes County. When the pandemic started affecting employment in April of 2020, Deschutes County had experienced some of the lowest unemployment rates in its history.

"Three-point-three percent was the bottom before the pandemic, and that was historically low, we had never seen rates that low in Central Oregon's history, and definitely not in Deschutes County," said Damon Runberg, a regional economist with the OED.

Full employment for Deschutes County, Runberg said, is met at about a 4.5% unemployment rate. When the rate goes too low it can be difficult for businesses to hire, and when it's too high that's usually a sign there aren't enough jobs for workers to fill. Full employment is defined regionally, and Central Oregon tends to have more unemployment.

"Our rates of unemployment in Deschutes County, or even Crook County or Jefferson County, our neighboring rural communities, on average, tend to have higher rates of unemployment than the national or the state numbers, and that's not because we have a weaker economy or anything like that—we have more seasonality in our economy," Runberg said. "Impacts from the tourism sector, construction, agriculture, all those together mean that we have a more natural higher rate of unemployment."

“I think a lot of people hear that and think that it’s a wishy-washy labor force or people not wanting to engage in the workforce or be non-committal, whatever it might be. It really has nothing to do with that. It has almost everything to do with people quitting jobs and moving into other jobs. They’re not leaving the labor force for the most part.”—Damon Runberg

tweet this

The biggest recovery is in the leisure and hospitality industries, which lost 54% of its workforce in the immediate shock after COVID. Now it's down about 3.5% from pre-pandemic levels.

"It's pretty dang close to being recovered when you consider that over half the jobs were shed. That's quite a feat," Runberg said.

Manufacturing and construction also rebounded well, but retail trade lags behind pre-pandemic employment numbers by about 520 jobs. Still, these numbers don't align with the prevailing notion locally that there are still too few workers to fill available jobs.

"I think a lot of people hear that and think that it's a wishy-washy labor force or people not wanting to engage in the workforce or be non-committal, whatever it might be," Runberg said. "It really has nothing to do with that. It has almost everything to do with people quitting jobs and moving into other jobs. They're not leaving the labor force, for the most part."

The Bureau of Labor Statistics reported a record-breaking 2.9% of the workforce quit their jobs in August, only to be surpassed in September when 3% quit. Oregon has one of the highest quit rates in the country.

"Because of the high demand for labor, there's lots of opportunities for people to change a career, move into a position that has better pay or has better working conditions," Runberg said. "When there's a really high demand for labor and the supply is low, it's the type of leverage that workers only get in relatively small periods of time. And taking advantage of that is not a terrible idea."

Wages rose for most income levels, but especially for people making lower wages. But those wage gains are largely being diminished, even as wages continue to rise.

"What's interesting in today's market is the nominal wages continue to go up pretty aggressively, nominal being non-inflation adjusted wages. However, because of the last six months of relatively high inflation numbers we've seen, that has eroded those wage gains, and so the inflation adjusted wages actually stopped growing. So, we've sort of flattened out there," Runberg said.

Runberg said Deschutes County's economic recovery was atypical when compared to other Oregon metros, most of which haven't recovered as quickly. Portland, for example, has only recovered 72% of its jobs lost during the pandemic. States with fewer public health mandates reached pre-pandemic employment earlier than those that had strict masking and distancing mandates. This recession differed from others in that it was more tied to policy than is typical.

"Normally a recession happens and it hits economies to different magnitudes or different levels, because the industry concentration that that economy has. This was this was a little bit of that in the sense that the leisure sector was hard hit across the country, regardless. But it was hit to a greater or lesser extent, depending on those policy responses," Runberg said. "In Oregon, which was a state that had sort of more aggressive public health measures, we are unique to have been recovered, especially when you consider that Deschutes County was one of the hardest hit in the initial job losses."