When Bend teacher Travis Overley was a student teacher at Bend High School, teaching in front of a class of more than 40 students was common. At Bend High, however—one of the oldest buildings in the Bend-La Pine School District—Overley says it wasn't just the size of the classes that stood out.

"Kids are sitting on the counters, they're sitting on the floors because there's not enough desks, ceiling tiles crumbling, stained walls, the bathrooms aren't up to date," Overley describes. He says the passage of recent local bonds took care of some of those issues, but there are still areas of concern around things like class size and upkeep of some of the older buildings in the Bend-La Pine school district. "They've done a lot of work on a lot of other buildings, but particularly the older buildings, so much of the work that's being done is cosmetic," Overley says. "They want people like us, when we walk in, to see, you know, like, 'OK, this school looks better,' but if you get to some of the other stuff, the radon, the mold, the dust...obviously, the seismic problems that there's a potential to have..."

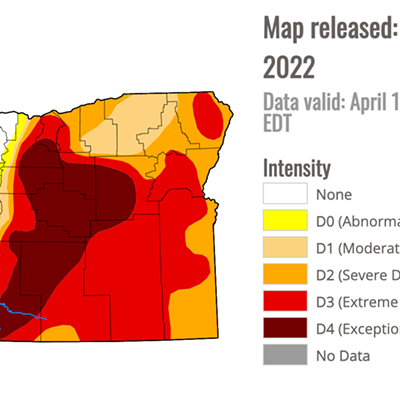

It's situations like those that prompted the Oregon PTA, Children First for Oregon and the Oregon Education Association to issue a report Aug. 22, calling for the state to address $7.6 billion in deferred maintenance in school buildings statewide. According to the report, a "steady disinvestment" in public education has left school infrastructure in a neglected state, forcing districts to make tough calls about where to spend. The report cites lead exposure, lead-tainted water, radon and poor indoor air quality, seismic risk and mold, mildew, dust and other asthma triggers as the "priority areas" needing immediate attention.

In light of recent tests finding radon and lead in Portland school buildings, the "safe schools" report is just the latest in a public outcry around statewide public school funding. Comparatively speaking though, some in Central Oregon still look at things as the glass half-full.

"I think we're really lucky in Bend-La Pine because when bonds come up and people say we need to build a new school, everybody chips in. We say 'Yes, great, let's build a new school.' So I think the facilities in Bend La Pine right now are in a good place," says Collin Robinson, a parent of two students in the Bend-La Pine district and president of the Oregon PTA. Still, Robinson isn't expecting the district to rest on its laurels.

"The concern is if we continue kind of a disinvestment in maintenance—or the deferred maintenance—what happens in 20, 30, 40, 50 years, if things change, if we stop building new schools, if we're not taking care of our current facilities," Robinson says.

Chief operations and financial officer for the Bend-La Pine district, Brad Henry, sees Bend facing not so much funding issues, but challenges with capacity and growth.

"I think we do a good job of maintaining our facilities we have facilities that are 100 years old and are still in use," says Henry. Compared to the rest of the state, however, Henry says "It's not equal across the board because some communities have the resources and the community support to maintain their facilities at a level that is safe and is appropriate for the instructional model they're trying to present."

From the Bend-La Pine district perspective, the approach seems to involve vigilance and planning. To cover future maintenance and repairs, the district relies on a 20-year overall plan, renewed every five years. In addition—at least partly in response to the Portland school water crisis—the Bend-La Pine school district conducted lead tests in all district schools this June. All tests came back clear, says school board member Andy High.

Still, not all schools get a completely clean bill of health. High gave Kenwood School, home of Highland Elementary, as an example of one building that's been identified as having asbestos — something the district has a plan for when it's time to remove it.

"We have a safety assessment officer that goes through and checks out what's going on in the schools and how to prevent accidents from happening, working not only with our staff, but students," says High. "If there's an unsafe environment I know that the goal is to get it fixed immediately. So if something breaks, we find that we're definitely more proactive than reactive...and I don't know where Portland is at but it feels reactive."

For teachers on the ground, there's still more to be done.

"Day after day, there's more reports coming out highlighting the incredible need," says Overley. "Here we are, $7.6 billion shortfall in terms of deferred maintenance in our schools, so it's pretty baffling."

Disparities in the District

Overley also points to disparities in school facilities as a problem affecting students here in Central Oregon. Some schools are brandnew, while others are decades old—and that's often impacted by zip code. In Bend, Overley points out the stark contrast between older buildings like Pilot Butte Middle School and Bear Creek Elementary, and brand-new schools such as Pacific Crest.

"(Students) don't have a choice in where they were born or what side of town they were born in; they just show up every day. They're walking into the doors of something that's not setting them up for success," Overley says. "If you look at the graduation rates, if you look at the funding per pupil, we're seeing the results, we're seeing the consequences of all that."

Still, school board member High maintains that it's a more holistic formula that makes up a successful school. "All of us would love to have that brand new school for every one of our students, but it's also making it, creating an environment where you're still proud to be in that school," High says.

The Class Size Dilemma

Meanwhile, large class sizes continue to be a huge problem.

"Our voters and our community really understand and support what's going on from the schools and the building of that, I think if I had a choice...that they would give (money) to continue to reduce class sizes and hire more teachers," says High.

Last school year, Overley—who now teaches social studies at Bend's Summit High School—launched a crowdfunding campaign to pay for new desks in his classroom. He admits that the purchase was more of a "want" than a "need," but maintains that the desks were crucial to allowing his students to see maximum success. The new desks are on wheels, allowing students to move around the room, and allowing Overley to reconfigure the room to better meet the needs of a large, changing class. This school year, Overley says his smallest class size is 39 students.

"A 50 by 50-foot room and you're putting 39 kids in that room, 39 teenagers, and I'm in the best-case scenario—so I actually have it good. I actually have a desk for all of my students, they have a place to sit, they're not sitting on countertops," Overley says.

Oregon PTA president Robinson is clear on where more support needs to come from—and it's not local bonds.

"It becomes a budget issue and that starts from the top. That starts in Salem," Robinson says.

MEASURE 97

Since 1990 and the passage of Measure 5—which shifted the burden for funding schools onto state revenues rather than on local property taxes—state funding for education has seen a continual decline, according to the OEA/PTA/Children First report. So how to dial back that funding gap? Among the potential solutions is Oregon Measure 97, a hotly-debated item on the Nov. 8 ballot that would establish a 2.5 per-cent tax on corporate gross sales over $25 million.

Even in the Bend-La Pine district, educators and policy makers are divided on the issue. During its meeting in July, the Bend-La Pine school board took an official position against Measure 97.

The main issue—at least for board member High: "There was no direct correlation to anything that was actually going directly into schools and or direct spending or support," High said. "I'm a small business owner myself, that, the regressiveness, just really scared me."

From his position in the Oregon PTA, Robinson disagrees.

"Oregon mandated the QEM, the quality education model, so many years ago, and we've never fully funded it because we gave the legislators an out. We said, 'If you guys give us a report about why you can't fund it, that's good enough.' That's not good enough. I think if we are funding our schools statewide to the quality education model, a lot of this stuff kind of goes away.

"When it comes down to it, that's really, that's our best shot right now to make this happen is Measure 97," says Robinson.

Marijuana's Role in School Funding

When voters approved Measure 91 legalizing recreational marijuana sales in Oregon, many looked forward to the promise of 40 percent of pot taxes heading toward the state's common school fund. As of July 31, the state had raked in $25.5 million in pot tax sales. With deferred school maintenance reportedly already behind by the billions, funding schools with pot taxes is far from a comprehensive solution—and it also comes with questions.

"Hopefully they allow local control for us to decide what's best to use it on," High reflects. "What Sisters needs for their resources may be different than Bend La Pine, and Redmond's needs are different than Sisters."

Robinson agrees that local control is an issue they'll be looking to when state budgets are allocated.

Even with those potential windfalls, however, there's still a long way to go, Overley says.

"And so let's say measure 97 passes. Are our problems going to be solved the day after election day? Of course not. That's where we need the citizen engagement. Like, get to your school board meetings. Get to your PTA meetings, go into the classrooms, ask teachers what they need."

What they need most, Overley says: "We're not asking for much. We're just asking for adequate funding."

*Figures from "Decades of Disinvestment: The State of School Funding in Oregon," courtesy of Oregon PTA / Oregon Education Association / AFT Oregon