The sun is barely up and I'm launching.

Current—2,500 cubic feet per second of it—catches my fin. I had hoped to run Clarno to Cottonwood on the John Day River twice already this spring, but it didn't work out. As my standup paddleboard (or standup paddle raft, as I like to think of it) gently coasts over the first riffle, the relief of pulling the trigger on a mission settles over me. Redemption.

Getting time on the river, privately and professionally, is a priority for the community in which I circulate—but it might be a different story if President Lyndon Johnson hadn't signed the Wild & Scenic Rivers Act in 1968. Upon doing so, he stated, "In the past 50 years, we have learned—all too slowly, I think—to prize and protect God's precious gifts... An unspoiled river is a very rare thing in this nation today."

At the time, Congress stated, "The National policy of dams and other construction at appropriate sections of the rivers of the United States needs to be complemented by a policy that would preserve other selected rivers or sections thereof in their free-flowing condition to protect the water quality of such rivers and to fulfill other vital national conservation purposes," as noted in the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act.

Today, 12,734 miles on 208 rivers in the U.S.—or a little more than one-quarter of 1 percent of the nation's rivers—are protected under the Act. Compare that to more than 75,000 large dams across the country, modifying at least 600,000 miles, or about 17 percent, of rivers in the U.S. It's a start, but saying the dam policy complements the Act's policy might be a stretch. Still, Oregon's rivers get more protection than other locales.

En route to the Grand Ronde River earlier this spring, fellow boater, Hank Hill, explained that multi-day raft trips on the east coast aren't an option the way they are in Oregon. There, rivers are chopped up with dams, or are privately owned. There are 58 National Wild and Scenic River designations in Oregon—more than any other state.

CentralOregonWildandScienic.org, a website maintained by a host of public and private agencies, lists the protected rivers in Central Oregon as the Metolius, Deschutes, Little Deschutes, Big Marsh Creek, Crooked, Whychus Creek, Crescent Creek and the John Day.

Alone on the John Day

With each paddle stroke, redemption coursed through the conduits of my body like braided streams, my heart the ultimate aquifer.

I mentally briefed myself on the plan one more time. Clarno to Cottonwood, 70 miles in one night and two days. Shuttle scheduled at the take-out by 2 pm the second day. Key in the gas cap, payment under the floor mat (a familiar protocol to any boater). Plan A: 50 miles the first day, to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act. Plan B: Split the difference, 35 miles per day. Plan C: If afternoon upriver winds rage, make it a two-nighter. Whether A, B or C, all systems go.

The scenery forced my brain out of planning. As pasture gave way to towering basalt terraces, sometimes scorched red and oxidizing, sometimes shrouded in a soft and endless veil of fuzzy grass, the longest undammed river in Oregon hypnotized me.

Between walls of lava, sandwiched in a canyon, I met the Clarno and Basalt Rapids. Some sources call Clarno a Class 3 to 4; some sources call Basalt Class 2 to 3. (For those unfamiliar, Class 1 is the easiest rapid; Class 6 the toughest.) I called them both a good opportunity to get detailed on how to read a river map. Following the beta for the best scouting location would be critical if I didn't want to end up in the middle of a whitewash, sight unseen.

Running the rapids

A few things happened to me as a kid that left me a little terrified of water, and I knew some of those memories would surface during the trip.

Scouting and choosing safest methods for running the rapids ended up not being that big of a deal, but that aspect of the journey had been the most intimidating, back home, planning on my couch.

The gnarliest bit was when, just after Clarno Rapid, adrenaline pumping, I unintentionally slapped myself with the T grip on my paddle. For the remainder of the trip, my right-side jaw was a little achy, in the same location where I had a tumor removed 10 years ago.

I felt a big victory at river mile 16 when I could say I had successfully navigated the hardest sections of water. Finding myself dropping over Lower Clarno Rapid backwards notwithstanding, Wild and Scenic though it was, clutching my paddle, waiting to smash through a huge hole in reverse, I found myself stalled out in an eddy at the base of the drop, facing upriver, unmoving. It felt amazing to have inadvertently avoided what felt like certain mayhem, however unplanned, however sloppy and accidental. MADE IT!

From here, it was all downhill (but isn't it always on a river?). I enjoyed the playful rapids, one after another, coming at least every mile, sometimes timed with a bend in the channel, sometimes associated with a constriction.

As I punched out miles, I flipped the pages of the map and read the interpretive boxes sprinkled throughout. One such notation mentioned there once was a river boat named the John Day Queen. I adopted this title for my own vessel and shouted it out frequently.

Before I knew it, 11 hours had flown by and I was 50 miles deep. Mission accomplished.

Day one down

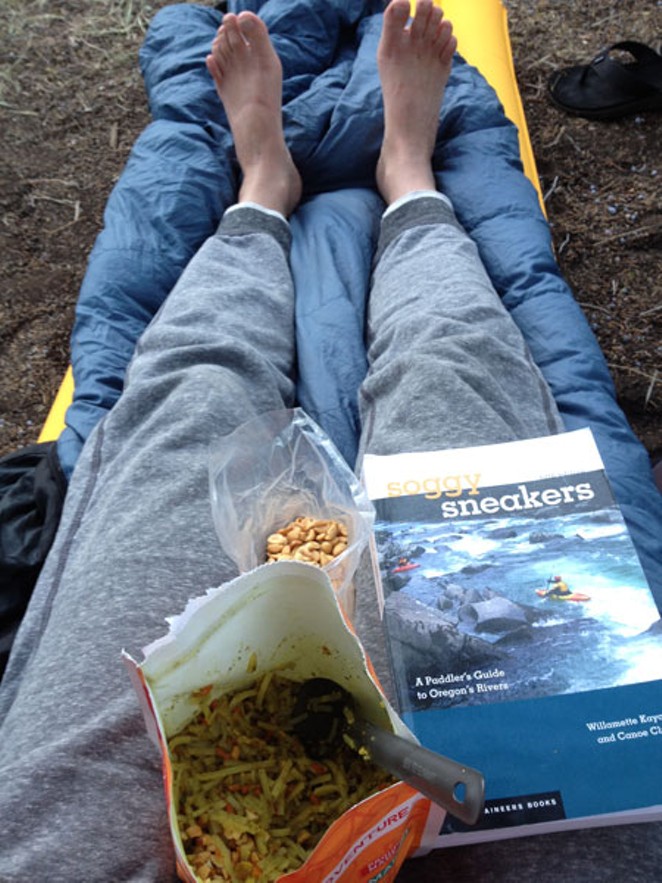

I slept the deepest sleep of my life. In my slumber, the river de-fragged and reformatted my hard drive. Disempowering memories were swapped out and replaced with the day's most empowering moments. Fierce female emerging.

The next morning I paddled three and a half hours to the take out. Arriving at noon, I beat the shuttle by two hours. In total, a 29-hour, 15-minute trip. When, at 2:30 pm there was still no sign of my vehicle, I hoofed it over to Cottonwood State Park and flagged down ranger Stan for help. He kindly offered the use of a satellite phone. At 3:30 pm my chariot arrived, and I began the painless process of de-rigging a paddleboard.

It's not just a fear of water that can spook me running rapids. I got the sh** beaten out of me when I was a kid, too. A lot. I got dragged through department stores by my forearm and forced into bathroom stalls or behind curtains. My mom was mild in public. The Class 4 and 5 beatings happened at our government-subsidized duplex in the Beaverton projects. There's a humiliation in child abuse akin to drowning.

The abuse came complete with poverty—and not just financial. I grew up hungry, first for food, then for knowledge, challenge and experience... for a shot at what I saw other kids had.

I found outdoor recreation late in life, giving me a wealth and support I had never known. It's been an outlet, a redemption of sorts. What my fate would have been without the playground of public lands and Wild and Scenic Rivers, I cannot say.

After my trip, I received an email from a prominent local inflatable paddleboarder. He laughed at me, through the written word, for suggesting that I might be capable of running Clarno to Cottonwood. He went on to berate my perspectives on downriver paddleboard touring. To be sure I understood his authority, he wrote out his resume for me.

The funny thing is, his email arrived after I completed the mission. It made me wonder why people like to guard access and pretend only a certain chosen few are allowed admission.

What my fate would have been without the playground of public lands and Wild and Scenic Rivers, I cannot say.

tweet this

Reality abides. Downriver paddleboarding isn't that hard—especially if you've ever faced any kind of real life adversity, like being homeless or having authorities intervene because your teachers can tell you're being neglected.

In time, in the spirit of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, I hope where there is exclusion in the paddle and outdoor industry, we can collectively grow toward access and inclusion.

When I think of the threats to public lands—particularly Wild and Scenic Rivers—that the current White House Administration poses, I think of all that stands to be lost. I think of all the little girls in our country growing up like I did—little girls who need a playground.

Bend's Wild and Scenic controversy

And the administration isn't the only challenge posed for these Wild and Scenic Rivers—even locally.

In Bend, the possibility of a pedestrian bridge over the Deschutes south of town, along the Wild and Scenic portion of the river, has river advocates concerned. Oregon Wild states on its website, "Building a bridge on the protected stretch of river would require weakening river protections afforded by the State and Forest Service. In a day and age when our public lands are threatened at all levels, whether it's Monuments in Utah, State Forests in Oregon, or Wildlife Refuges in Alaska, any weakening of public lands protections is a red flag and potential slippery slope bad precedent." Are we learning all too slowly, as President Johnson feared?

"I asked myself how we would get people excited about celebrating a piece of legislation," said Executive Director of Discover Your Forest, Rika Ayotte. "Of course we all can very easily celebrate the rivers we love, but how do we make sure that we truly celebrate the laws that protect these amazing resources. I think that people are more aware than ever that protections for our public lands are not automatic or guaranteed and that it is so important that we as citizens participate in the civic processes to maintain these treasured places."

It's the adventure

People ask me if traveling solo on the river is scary. I've known many scary things; being alone is not one of them. On every journey there are a few big rapids that make me pause. But I wouldn't forgo the adventure for fear of confronting these moments. They are only a quarter of a quarter percent compared to, as President Johnson might say, the precious Wild and Scenic gifts the rest of the river holds.

Local river advocates have a host of activities planned to celebrate the Wild and Scenic Act's 50th anniversary through the end of the year.

To see a list of local Wild and Scenic rivers and a list of events, check out: centraloregonwildandscenic.org.