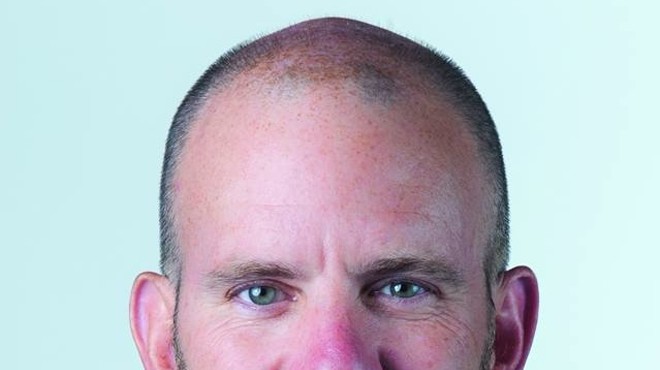

On a recent Monday morning, City Manager Eric King was visiting a local elementary school when the first grade teacher asked her students what they think a city manager does. For a parent who is a doctor or firefighter or grocer, the question would be fairly straightforward. But this question baffled the students for a moment; then, the students started throwing out suggestions, like tossing darts at a bull's eye.

"Clean up our toys," one child offered. "Keep us safe," said another. What the young citizens seemed to grasp was that, as city manager, King is essentially responsible for the nuts and bolts of keeping the city running smoothly, a civic lesson that is perhaps not too far from what many adult residents know about the inner workings at city hall—and about who truly has his or her hands on the levers of power, and how they stay there.

Case in point: After the Source recently reported that the City of Bend had determined not to renew a lease for Mirror Pond Plaza with Crow's Feet Commons, some riled up readers posted suggestions that Bendites need to "vote out" city staff of whom they disapprove. But staff—those individuals paid to help run the city's various departments—are not elected officials. Only city councilors are elected.

Moreover, the scope of what city hall can and cannot do—and who is doing it—does not always seem clear to residents. For example, candidates for city council often campaign on improving education in Bend (an issue managed by the school board), or make promises about what they plan to do about Mirror Pond (an issue more likely to be handled by Bend Park & Recreation, an entity with completely separate funding and governance).

How does city council work then?

Common among small-to-medium-sized cities, Bend has what's known as a council-manager form of government—a format modeled after the private sector. The city manager, King, has a function similar to a chief executive officer (CEO) and the city council is like a board of directors. Council shapes policy, while the city manager executes it. Of course, that division of labor isn't entirely non-porous. As city manager, King frequently makes policy recommendations to council. And those seven members have the power to hire and fire the city manager, as well as the municipal judge.

Does that mean the city manager has more power than the mayor?

How much influence the mayor wields has more to do with personality than the powers of the office, but when it comes to authority, the mayor has very little. The mayor and mayor pro-tem (similar to a board president and vice president) are elected by their fellow councilmembers, not the voting public. While the city manager runs the city, the mayor runs city council meetings. That isn't the case in all cities.

"When people think of city government they probably think of the 'strong mayor' form of government, where the mayor runs the show," King explains.

In this model, more common in large cities such as Seattle, Chicago and New York City, the elected mayor is the city's chief executive officer and has veto power over the legislative decisions made by city council. This type of government is based on the federal constitution structure.

King says that the city's charter—a constitution-like document that guides Bend's approach to governance—was last reviewed in 2011. At that time, there was some discussion about changing not the model of government, but the way in which the mayor is elected. Council voted 4-3 in favor of continuing to elect the mayor within council, as opposed to letting the people vote, King says.

As Bend continues to grow, it's possible its government will change with it. While King says he doesn't necessarily see Bend moving away from the council-manager format anytime soon, the city could opt to enhance the responsibilities and compensation of city councilors, for example.

The golden rule: He who has the gold rules?

Currently, Bend city councilors serve as part-time volunteers. They receive a $200 monthly stipend for their contributions, but are not held to a specific number of hours, nor do they have offices at City Hall. City councilors say they spend an average of 20 hours a week on council business (though they say that number can reach up to 40 hours some weeks); at an hourly wage, that would pencil to about $2.50 an hour. By way of contrast, City Manager Eric King makes about $160,000 a year.

In some cities with a council-manager model, such as Eugene, councilors receive more substantial compensation, with the mayor getting a salary of up to $20,000-$30,000, King says. This year, city council candidate Ron Boozell proposed a local ballot initiative to increase compensation for city councilors from $300 a month to $30 a day—about $600 a month, or $20 an hour for 20 hours a week of work—but failed to get sufficient signatures to get the measure on the ballot.

"We're on the cusp," King says. "I think it's a good conversation to have, 'Is this the right structure?'"

Power to the (privileged) people?

While most city councilors have part or full-time jobs, these jobs are flexible enough to allow councilors to attend mid-day committee meetings, and conduct other city business during standard working hours. As such, it's not feasible for everyone to serve on council. People working full-time jobs with inflexible schedules or those who must work more than 40 hours a week to get by, for example, would likely struggle to meet the demands of this type of public service.

Even those councilors who run their own businesses say it's challenging to achieve work/council/life balance.

"I have an education research and consulting firm, Caldera Research LLC, which I run with my wife, Naomi," says Councilor Victor Chudowsky. "Frankly, there is no balance. My council duties directly detract from my work and family, and it is often difficult."

Councilor Mark Capell, who owns computer services company CMIT Solutions, says he's lucky to be in a position that allows him to take on the sometime full-time job that is city council.

"At work, I have to be very efficient, and fortunately," Capell says, "I have really good employees that make it easier for me fit in city business."

City Manager King acknowledges that drawback to the current structure, but adds that on the flipside, many would argue that public service should be just that—service, and that increasing compensation could bring people into the job for the wrong reasons. As a number of candidates for higher offices running against incumbents are fond of reminding voters, the founding fathers intended for public service to be a short-term departure from one's regular working life.

Who gives out the keys to the city then?

Though the terms are relatively short and the compensation rather low, the decisions made by city council impact residents in meaningful ways. From setting utility rates and determining methods of water treatment to determining how the city's funds are spent, they set policy and funding priorities for the city that ripple out into many aspects of daily life.

But council's scope of authority isn't unlimited. Council is the legislative body, while the city manager handles administration, so councilors have little to no say over administrative or staff issues. For example, the city manager oversees the leasing of city-owned properties, such as the Rademacher House currently occupied by Crow's Feet Commons. City council sought clarification from city staff on the issue, but it is ultimately not under its purview. It can, however, change policy regarding the leasing of public rights of way. That's because Bend City Council's responsibilities are primarily centered around infrastructure—it does not have oversight of the library or parks, which are governed by their own boards.

And while some of the issues council considers may seem mundane—such as where to place crosswalks or the difference in code between the words "should" and "shall"—the councilors do not always agree. The recent debate over whether to adopt membrane or UV filtration for Bend's water treatment is a prime example of the differing perspectives among councilors, and by extension, the importance of voting for candidates that reflect the values and priorities of the community.

"City council ensures the issues we're tackling are meeting the needs of the community," King explains.

This year three seats on council are up for grabs—the one vacated by candidate for Deschutes County Commissioner Jodie Barram, and the two seats currently occupied by Scott Ramsay and Mark Capell. Eight people in all are running for the three seats. For more information about the candidates, see page 7 - 9.