Just having turned 90, it occurs to me that I've been working with golden eagles over 60-plus, years and it continues to be an adventure. I started reading about them in William L. Finley and Herman T. Bohlman's great bird books in the late '30s.

I also recall back in the '50s, when the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service discovered a gang of trappers using a lethal poison known as 1080 (a weapon of mass destruction, left over from WWII) to kill predators—also killing everything else that got into the bait—eagles included.

That got me started checking predator control 1080 poison stations. I found dead eagles, flickers, magpies, ravens, mice, skunks, badgers and even songbirds poisoned by federal trappers attempting to eliminate coyotes from the face of the Earth.

Boy, did that backfire! There are more coyotes in North America today than in the '50s. They're living in Los Angeles, Chicago, downtown Boston and Maine. On top of that, there's now a crossbreed coyote, wolf and wolf/dog in the Northeast that's starting to wage war on humans.

Just a year after I rolled into Bend on my grand old 1947 Harley, I found an adult bald eagle dead near a 1080 poison station. It really got me upset, so I wrote a letter to the head of USFWS, voicing my concern.

I've memorized the response: "Dear Mr. Anderson, Thank you for your concern for eagles; they're shot as a nuisance in Alaska..."

And that did it. From that day on, people, companies or agencies who kill eagles are not my favorite. The good thing is, people who respect the role of wildlife in nature often get together. In the mid '50s, just a year after I settled down in Bend, I met Avon Mayfield, an Oregon State Police wildlife officer who needed someone to climb a big yellow pine to retrieve two golden eagle nestlings that had been shot. I'll never forget the moment I handed Mayfield those dead eagles. He looked at me and said, "We have to put a stop to this, Jim."

He did his part, and then some, getting the guys who killed the baby eagles. Every time I learned of someone killing eagles and other raptors I'd call Mayfield at home. His first response was, "I'll be there as soon as I get my uniform on." He never turned me down.

In 1962, I got my federal banding permit allowing me special permission to band eagles. Every spring, banding golden eagles became a family high point, and still is. Today, my wife, Sue, and I are helping the Oregon Eagle Foundation conduct a 10-year survey on the status of golden eagles in the state, keeping an eye on over 150 breeding sites, with the help of a few volunteers.

Back in the '60s, my oldest sons, Dean and Ross, became part of the annual raptor banding at a very young age. From the time they could walk they were into eagle banding (and capturing snakes).

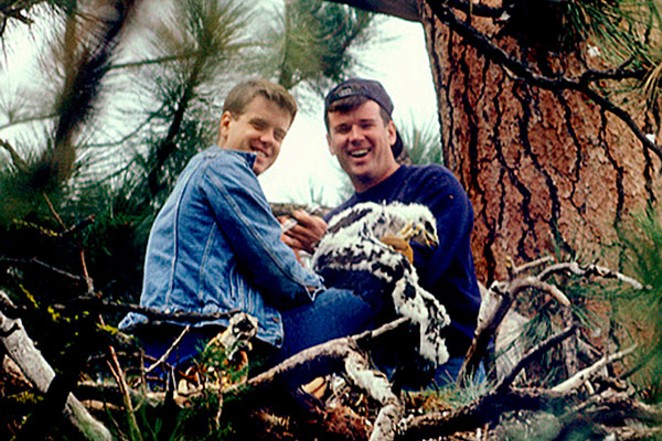

One of the photos featured here shows both of them in an eagle nest during one of the lighter moments of banding nestling golden eagles. It was the first nest I visited in the '50s, and produced many eagles — but I fear the eagles that were using it are dead. During banding two years back, both eaglets from that nest died of Brodifacoum poisoning, another poison developed to kill, without anyone taking into consideration the collateral damages. Dean's demonstrating his crass humor because Ross was the innocent bystander of one of the perils of handing nestling eagles: he got a blast of excrement across his legs. I'm told falconers judge the strength of their birds by how far they can squirt excrement, known as, "slicing."

"Dear Mr. Anderson, Thank you for your concern for eagles; they're shot as a nuisance in Alaska..."

tweet this

A couple of years back, Sue and I were in Lake County and discovered three young in a huge nest, very close to fledging. "Boy," Sue said, "we gotta band those youngsters or they'll be gone before we can get back."

The next day we got to the old lava cliff where the eyrie was located. Climber Langdon Schmidt got into his ropes and sent the first of the tree young eagles down. I carefully opened the bag, revealing a young, energetic golden eagle of approximately six weeks of age, fully feathered and about two weeks from fledging.

I reached into the bag and grasped both wings tightly so the bird couldn't get loose and injure itself, or knock my head off. Its beautiful head came out of the bag, staring at Sue, who was shooting pictures as fast as her Canon could go. With a lot of effort and care I lifted the rest of the eagle clear, holding its wings tight against the 9-pound body.

At that moment an event took place that's never happened to me in my years banding eagles. This giant baby—a female, judging by its size—looked Sue right in the eyes, hunched up, raised its tail and let 'er rip!

The force of her "slicing" was so strong that when the white and black excrement hit me I almost dropped her. The odor wasn't much, but the content was overwhelming. It tore into my shirt, went into my undergarments, and then, like a hot waterfall, descended into my britches, clear down to my socks.

Such are the lighter moments of banding eagles...