It's being touted as one of the most "significant restoration efforts in the American west," and it's taking place right in our backyards.

Reconstruction efforts got underway this month on a 1.5-mile stretch of Whychus Creek, a part of the Whychus Canyon Preserve owned by the Deschutes Land Trust. The effort is part of a multi-year reconstruction plan spanning a six-mile run of the Whychus tributary in the Deschutes watershed.

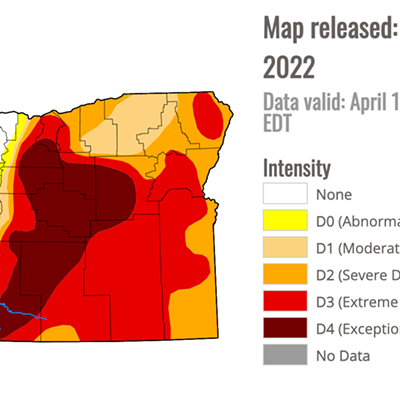

Before Whychus Canyon became a preserve in 2010, the creek bed ran dry most summers as a result of "over-appropriation," says Brad Chalfant, executive director of the Deschutes Land Trust. It's an effect of confining stream structures built by previous landowners, Chalfant says. Once upon a time, farmers built berms and funneled branching channels near the creek to avoid flooding. The ultimate result, however, was a loss of the benefits of flooding.

"Following the Christmas of '64 floods (all across Oregon), public agencies, including the U.S. Corps of Engineers, encouraged landowners to straighten and armor creeks and rivers, so that water moved through quickly and didn't spread onto the floodplain," explains Chalfant.

Isolating the floodplain from recharge meant no more shallow aquifers, which are critical to the health of riparian systems—those green sections of vegetation that grow near waterways. With that change, groundwater levels dropped and areas previously known as wetlands dried out. This domino-ed into loss of vegetation that provided shade and habitat for a wide range of wildlife species. Chalfant laments, "In other words, the whole system came unraveled."

Before the influences of agriculture, the Whychus Creek river environment was a mixture of narrow canyons and level meadows where the creek could spill over its banks. This spillover filled fluctuating wetlands, a valuable water cache that slowly drained throughout drier months. This provided diverse stream and side-channel habitats for fish to spawn, rear, and hide. Biologically speaking, those marshes were essential to the surrounding flora and fauna.

"They only occupy two percent of the landscape in a desert, yet 75 percent of birds rely on these areas for a portion part of their life cycle," says Ryan Houston of the Upper Deschutes Watershed Council.

The Whychus Creek project is borrowing many elements of its rehabilitation plan from Camp Polk Meadow Preserve (CPMR), including the use of large woody debris to create complex habitat for fish and wildlife in and around stream banks, as well as the practice of carving out and back-filling soil to promote free movement of water across the historic floodplain. In addition, more than 60,000 native trees, shrubs, wildflowers and grasses will be planted and seeded to facilitate stream shade, bank and floodplain stability, and habitat for wildlife.

Restoration efforts are made possible through the Deschutes Partnership, a collaboration between the Upper Deschutes Watershed Council, the Crooked River Watershed Council and the Deschutes River Conservancy. Chalfant says The Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs, Oregon Department of Fish & Wildlife and the Deschutes National Forest are also championing and contributing to the restoration.

Still, some question restoration projects in general, arguing the concept is subjective and it implies a return to a pre-disturbance state—which could be impossible to distinguish. Matt Shinderman, PhD, senior instructor/program lead in natural resources and sustainability for OSU Cascades, cautions: "When restoration projects are initiated, typically only half the ecological equation (i.e. what a system looked like, the structure) is known. This is then used to infer function, which isn't always ecologically defensible."

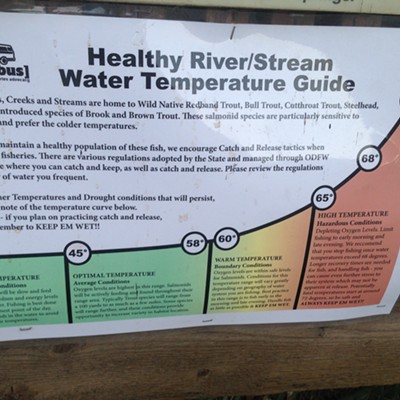

To see if the project is successful, Houston says, "We are focused on evaluating how we restore the ecological health of the river system. This includes health and function of wetlands and riparian spaces, quality and quantity of fish habitat and water quality. We will conduct long-term monitoring for these variables."

Shinderman's determination for structural success in the CPMP or the Whychus Canyon Preserve projects is whether riverbanks and vegetation are stable enough to withstand the disturbance of a 50- or 100-year flood event. Though Houston reiterates, "Having a stable bank isn't necessarily the goal; creating a dynamic river system that responds to change is."

Ultimately, preservation-centric organizations and their funders, partners and volunteers feel any restoration is flowing in the right direction, and say August's groundbreaking is definitely a step in the right direction.

Deschutes Land Trust

541-330-0017