A friend just got a delivery of bottled psilocybin, in the hopes of microdosing his way out of anxiety and poor sleep.

Another friend's been microdosing LSD for years.

"Participatory journalist" Michael Pollan's book, "How to Change your Mind" was the subject of a recent cover story in The New York Times Magazine.

And a psychology instructor at Oregon State University-Cascades will soon lead a four-part workshop, exploring whether hallucinogens will move from "demonization to legalization" in the coming decades.

Certainly this isn't one of those white-car, frequency illusion things, in which a person begins to notice something over and over after noticing it for the first time. With a local university now tackling this topic in its community learning offerings, it seems my microdosing friends have a lot of company in exploring hallucinogens as something more than a fun thing to do at a music festival.

But with the white-car phenomenon seemingly in full effect, I reached out to that psychology instructor to get his take.

The Changing Landscape of Recreational Drugs

Peter Sparks is the program lead and a senior instructor in the psychology department at OSU-Cascades, whose research delves into the connection between the mind and the body. When we sit down, he's quick to point out his interest in the topic of drugs comes from a biological point of view—a departure from Pollan, whose work has largely focused on cultural phenomena.Pollan's new book covers the history of hallucinogens—including how research into the potential benefits of psychedelics was stymied by the advent of the Controlled Substances Act and its listings of drug "Schedules" in 1970. Before that time, research and discussions around pychedelics flourished, with Albert Hoffmann and Timothy Leary among the biggest proponents of using psychedelics in therapeutic applications.

"The thing about the drug regulation is, essentially, if you're a Schedule 1 drug, research on it ends," Sparks said. LSD, marijuana and psilocybin, among others, are listed as Schedule 1 drugs, meaning they're considered to have a "high potential for abuse," and "no currently accepted medical use in treatment in the United States," and "lack of accepted safety for use of the drug or other substance under medical supervision."

Pollan's book also recounts his own experiences trying psychedelics for the first time, as well as the experiences of cancer patients and those with depression and addiction issues—who make their way to psychedelics including psilocybin (more colloquially known as magic mushrooms) and LSD to overcome mental and existential challenges.

How psychedelics work isn't fully understood—and since the CSA, researchers have faced bigger regulatory and funding hurdles in studying them. Yet a look at the list of articles and research studies listed on the U.S. National Library of Medicine's website reveals dozens of titles. A review published in the medical journal Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics in 2017 sums up the current landscape well in its title: "Psychedelics as Medicines: An Emerging New Paradigm." In the review abstract, the authors note a dramatic increase in scientific interest in "serotonergic psychedelics" within the past decade, citing "preliminary evidence of robust efficacy in treating anxiety and depression, as well as addiction to tobacco and alcohol."

"There's quite a few voices that are looking for reasons and justifications for, or evidence-based reasons why we should change the current schedule-based law and policy around these substances." —James Joseph

tweet this

Even as interest sees a resurgence, scientists admit they still don't fully understand what's happening in the brain during a trip. Some have described it as a de-prioritization of the portion of the brain that controls the ego. In one study, researchers found that when a person uses psilocybin, blood flow in the portion of the brain that governs fear and anxiety, the amygdala, is restricted.

Over at OSU-Cascades, Sparks says he's interested in LSD and psilocybin "because of the effects they cause in our minds. Most people talk about the rich colors and the fluid motions, the perceptual changes. Those may be fun to experience but are only mildly interesting to me. For me, the fact that LSD causes people to deeply contemplate, and feel a[n] interconnection and meaningfulness between events and to each other, is extremely interesting."

During his upcoming workshop, Sparks says he plans to explore how hallucinogens may soon head in the same direction marijuana has in recent years—from a concept many people rejected as "very bad for you, to not so bad to maybe good for you (in some ways) and even legal," Sparks wrote in an email. "This is mostly based on the fact that these few studies do show some potential benefits of use. This will only encourage more research, and that change may occur at a faster pace than marijuana because of our success with marijuana research."

When we met over coffee, Sparks seemed sure of the trajectory of hallucinogens moving from taboo to mainstream relatively quickly. "I do believe hallucinogens will be like marijuana in 1988," he said.

The path from taboo to mainstream

Sparks' predictions might seem fantastical at first blush—until you look at the progression of some of the research in recent years. For example, in 2017, the Food and Drug Administration granted "Breakthrough Therapy Designation" to MDMA—whose street equivalent is ecstasy or "molly"—for the treatment of Post-traumatic Stress Disorder, allowing the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies to enter into Phase 3 clinical trials. (Drugs go through four phases before being made public.) MAPS' mission: "developing medical, legal, and cultural contexts for people to benefit from the careful uses of psychedelics and marijuana."Sparks says another change in society in more recent years is the increase in the use of hallucinogens as a whole.

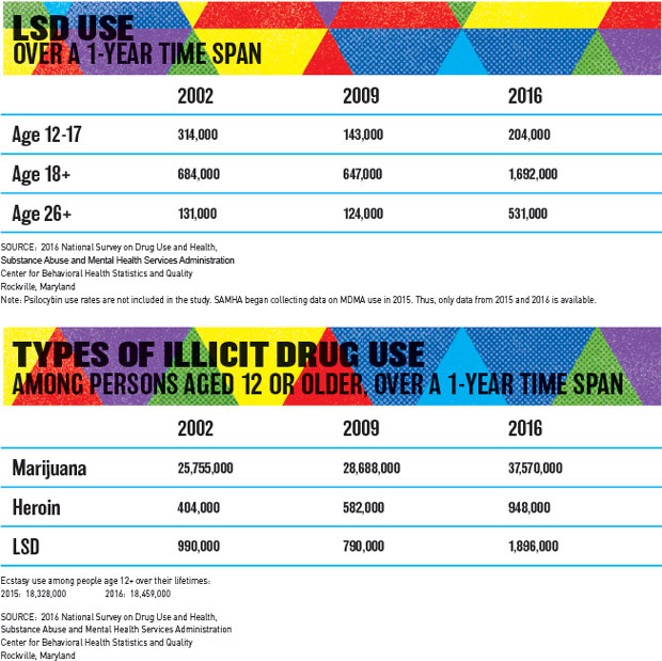

"For my class I look at prevalence rates for drug use, and I've been doing that for a decade," Sparks told me. "And just this last year when I was getting the new crop of data and sort of looking it all up, all of a sudden, I realized, hey, guess what, LSD use is going up. It's not kids, it's not 12- to 18-year-olds, or 17-year-olds, it's 18- to 25-year-olds, which is—for every drug out there, that's the highest group for use—but it's also 26 and above. It's something that already people are already starting to increase their use."

The Anecdotals

Both of my friends who regularly microdose are in their 40s. Both are professionals, successful in their fields; both struggle with some level of depression or anxiety. Neither have had LSD or psilocybin recommended to them by a doctor—few doctors would risk a medical license to recommend such a thing—but there was enough of a buzz around the potential benefits of microdosing that they're trying it."Certain things that used to cause me anxiety and stress, that were superfluous in my life, are now...zero f*cks given to them," says Sunset (not his real name), who's been experimenting with psilocybin for the past several months.

Microdosing, as its name suggests, involves taking small doses of a substance over a longer period of time. In Sunset's case, his self-administered protocol is four days on, three days off.

As Sparks explains it, "The whole idea of microdosing is that when you take LSD, lots of things go on. You are having these visual experiences, but you also have these emotional experiences and cognitive experiences. So the idea of microdosing is maybe if there is less of it, some of these experiences will go away, leaving some of these effects." The idea isn't to "trip" and to feel psychedelic effects, but, in theory, to unlock the brain benefits scientists are just barely beginning to understand.

"There is no scientific basis," Sparks says. "Well, so, there's no, there's no preconceived idea that 'this will happen,' because we don't know as much about LSD in terms of why it creates those different effects, but definitely, there's this logical idea."

In the case of my two friends, both use a tincture that's been diluted to deliver a dose about one-tenth the strength of a usual dose. Naturally, I wonder, how do they know it's working? How do they know it's not? From what evidence are they basing their protocols?

"The use of acid and psilocybin mushrooms has been studied since the '70s or even the '60s and sometimes the '50s," Sunset explains, when I press him about scientific evidence. "There's some legitimate positive research in terms of brain chemistry and anxiety relieving tendencies with use of them at all dosage levels, including full dose levels."

In Pollan's book, his interviews with shamans and healers leads him to the conclusion that a "full dose" may be more desirable than a "microdose"—at least for the people looking for mental breakthroughs.

For both of my anecdotals, however, there's been enough buzz around the concept of microdosing that they continue to see where it takes them.

The spiritual guide

From a psychology perspective, Sparks agrees that some type of guidance can be helpful—and even essential.

"Generally, if you are trying to do something in a therapeutic way, your mind isn't working the way you think it's supposed to work, just like any kind of therapy, having a guide is helpful," Sparks said. "The same goes for Prozac. Prozac alone isn't going to do anything. It's Prozac plus therapy. The drug puts you into a particular mindset, but you have to understand what that mindset means."

Helping people understand their own minds and emotions is just one mission for Heather Laurie, a licensed clinical social worker who works in private practice, offering therapy services to kids and adults in Bend. I first met Laurie about 11 years ago, when she served on the crisis team for Harmony Event Medicine, a Eugene-based nonprofit helping deliver on-site medical and crisis services at music shows and events. Sometimes, her work involved "sitting" with someone who was having a bad trip.

Like other mental health professionals, Laurie says she never makes recommendations to clients about microdosing or other protocols—that's not the purview of a therapist in the first place, she says. Still, she does encounter clients who are trying psychedelics or microdosing on their own.

"I have a ton of clients who engage in recreational substance use and they don't have substance use disorders or anything going on—everything from PTSD clients that are 'sick of taking sleeping medications doctors have prescribed to me now, and I've found that CBD really helps me fall asleep and so now I'm using that and here's what my experience has been'—just listening through that," Laurie told me. "I have some clients that go to ayahuasca retreats and when they come back from ceremony they want to digest and download and process, and it's really neat and they're doing that on their own. And it's not a recommendation that I'm making in any way shape or form, but it directly ties into what we've been working on in terms of their trauma process and kind of integrating all that within themselves."

Similar to Sparks' take on Prozac, Laurie sees therapy as a vital tool for clients.

"It's not even the substances that the clients are bringing into the office, it's really counseling about spirituality, because a lot of the psychedelic stuff is very integrated into a lot of people's spiritual thing, and helping them connect with spirit in their own way," she said.

Plants as mental health medicine

The Oregon nonprofit, Eugene Center for Ethnobotanical Studies, draws a similar line between the use of psychedelic plants and a need for a method to process experiences. Its mission, as described on its website: "Potent Plant Conservation, Education, and Liberation.""Our essential mission is promoting global awareness of, and local acceptability of plant-oriented ethnobotanical psychedelics," says James Joseph, Director and one of ECfES' founders.

"We tend to emphasize, in our organization, mindfulness or a practice to go along with folks that may be choosing microdosing and/or using higher doses," he said. "It's becoming pretty clear that when used in a therapeutic context a psychedelic can be powerful clinical intervention. One of the doctors on our board says that a day doesn't go by that he doesn't receive notes and articles on the subject of psychedelics being important medical and psychiatric tools. The interest of the general public is pretty justifiable based on the efficacy of the plants and fungi — based on the chemistry and the scientific evidence indicating improved cognitive and somatic functions."

"The same goes for Prozac. Prozac alone isn't going to do anything. It's Prozac plus therapy. The drug puts you into a particular mindset, but you have to understand what that mindset means." —Peter Sparks

tweet this

Joseph, a military veteran honorably discharged in 2006, came into this work after witnessing the drug war up close.

"For a time, I was stationed down in Colombia, so I witnessed a lot of counter-drug operations, interdictions and also met some of the farmers that were growing coca there. I gradually developed an understanding of the ins and outs of what the U.S. policy in the region was attempting, and failing, to achieve," Joseph told me during a phone interview. "What really inspired me in terms of social justice, I thought, [it was] quite unfair that some of these coca farmers are being sentenced to death to supply an American appetite to keep up their habit of cocaine use. So, for me, the focus is on the mental health field with an emphasis on healing."

At this moment in time, the momentum seems to be moving in ECfES' favor, toward a society that sees potential in psychedelics as a healing modality.

A good example of that is Kate Brown's decision to sign HB 2355, a bill carried to the upper chamber by Sen. Jackie Winters, the longest-serving African-American woman in Oregon Senate history, which de-felonized specific Schedule 1 substances in 2017." Joseph said.

"There's quite a few voices—such as the United Nations, the World Health Organization, British Medical Journal, Royal College of Physicians of London, the City of Vancouver, B.C., Oregon Association of Chiefs of Police and Oregon State Sheriffs' Association, and the Deputy Executive Secretary of the Narcotics Control Board of Ghana, Africa, and the United Nations General Assembly—that are looking for reasons and justifications for, and sharing evidence-based reasons why we should change the current schedule-based law and policy around these substances."

Pills vs. therapy—or both

"I think, generally, you know, people have always kind of wanted an instant solution, which is an 'oh, just give me the pill, and oh, look, I'm cured,'" Sparks says. "I mean even aspirin, it doesn't cure you of your injury, it just reduces some of the symptoms. And drugs like Prozac probably aren't curing you of depression, but helping you cope with the symptoms, and therefore, be able to get on the path toward recovery. And therefore, it's really likely that LSD is not something that will likely cure you, but help alleviate symptoms. And what I think people should do is then think about what they need to do to make that permanent. And usually I would say it's more likely a sort of verbal counseling, versus some sort of pharmaceutical intervention."As a therapist, Laurie takes each experience as it comes.

"I'm really lucky – my clients have been pretty chill. And the majority of experiences they've brought into the office with psychedelics or microdosing, or any of those things, they're, qualitatively, they're giving me, 'this is working for me.' I'm like – cool, it's not my job to tell you to, or not to."