Author’s Note: I skied on the world pro ski tour for 6+ years. Ours was a wild, crazy, nutso lifestyle. To be young, single, traveling the world, ski racing and making money at it was a very special time in my life. TYLER PALMER, I LOVE YOU.

Part One: Reluctantly attending U.S. Nationals at Bachelor

In late winter of 1972, I was 21 years old. A couple of years earlier I had fought my way onto a spot on the U.S. Ski Team with my sights on the ‘72 Winter Olympics to be held in February of that year in Sapporo, Japan. It was now March, the Olympics had come and gone, and I simply did not make the final cut. “Coach’s decision,” I was told—but that didn’t heal the hurt and frustration I was feeling. I deserved to be on that team.

So, I was in Bend, Oregon for the U.S. national championships being held on Mt. Bachelor and was not feeling very enthusiastic. The next Olympics were four years away. I wondered whether the team would carry me for four more years. There were many fine, younger skiers coming up through the ranks and in the eye of the ski team I would be an old man by 1976. Did I want to commit four more years to an organization that didn’t have much faith in me? To make matters worse, I was not skiing well, starting to get that sinking feeling that I was at the end of my ski racing career and I saw nothing on the horizon to make me feel differently.

At the slalom race at Mt. Bachelor I disqualified on my first run and would not get a second run (in slalom you take two runs and combine your times to determine the winner). We were staying at the Inn at the Seventh Mountain, so I caught a ride down the hill while the rest of the ski team was still racing. I found myself alone in our condo, contemplating my future. I was sipping on a beer, casually thumbing through the latest issue of Ski Racing magazine and not paying particular attention to its contents. Then I turned the page and staring me in the face was a full-page ad promoting the last two pro races of the season, being held the next week in Steamboat Springs and Vail, Colorado.

Pro ski racing was in its infancy, having been started a couple years earlier by Bob Beattie, who was best known as being the head coach for the men’s U.S. Ski Team in the 1964 and 1968 Winter Olympics. He was also a commentator for ABC’s “Wide World of Sports” and, along with Frank Gifford, called the 1976 downhill run by Franz Klammer at the Innsbruck Olympics. The pro tour was starting to take off with a completely different format than amateur racing, where one racer goes down one course at a time. The fastest time wins. In the pros there are two identical courses set side by side, 12 feet apart with jumps built into the courses. Racers compete head to head and winners are determined by simple elimination. I said to myself “Ya, pro ski racing, that could be the ticket!”

Bob “Beats” Beattie had already recruited some Olympic team members for the tour, including Spider Sabich, Hank Kashiwa and Tyler Palmer. Of the three, I knew Palmer best. Sabich was the only one of the three that was doing anything on the tour, having won the overall title the year before. In my heart I wasn’t ready to quit ski racing; I just thought there was something bigger in racing for me. I didn’t know what it was, but I was only 21 and I wanted more. Be careful what you wish for.

I somehow tracked down Bob Beattie by phone that afternoon. I told him of my intentions to leave the ski team and come to Steamboat. He was quite clear that I was welcome, but I would have to pay $100 to join the Professional Ski Racers Association. And just because I was coming from the ski team, I would be shown no favoritism. I would have to go through all the preliminary qualifying heats before I would be ceded into the money round. That turned out to be four races before I qualified….

Battie made it perfectly clear that Kashiwa and Palmer, just off the Olympic team, were struggling with the pro format. Beattie and I had met a few times and I knew him enough to know he was giving me the straight story. I thought about it for a few minutes, did the pro-and-con comparisons, came up with a lot of pros and damn few cons and so it was decided onward and upward to the pros.

I had just one small hurdle to overcome. I needed to get to Colorado from Oregon and had about $10 to my name. I figured it was going to take $300 to get to Steamboat, pay the association fees and leave me a little left over for food and beer. The only person I could ask for that type of a loan was my mother, who was born and raised in Germany, prior to and during WWII. She met and married my dad, an American GI, at the end of WWII in 1946. My parents divorced when I was 14 and she was old-school German. I knew that she would want me to go back to school if I left the ski team. Plus, the Vietnam War was in full swing and if I didn’t go back to school, I would lose my student draft deferment. I knew this was not going to be an easy phone call, so I practiced my story a few times before making the call.

We started out exchanging typical pleasantries and I started to bring her up to speed on what I was doing, telling her about the pro tour and how I wanted to go to “Steam….”. That’s as far as I got; I didn’t even get to say “Boat” before hearing an emphatic “NO!” and an ear full about ski racing as a dead-end street and how I need to get back to school before I lose my deferment. She would not let it go. I received a verbal tirade about Vietnam, how the whole “pro ski” thing was a big scam, that I was now 21 and needed to grow up and get serious about my life and that there is no way in hell she was going to loan me a dime to go “traipsing” across the country to this “Oceanboat” place to go ski race. I politely corrected her and said “It is Steamboat.”

Then I proposed that she let me go, and if I failed I would make a beeline to Denver and register for spring quarter with plenty of time to not lose my deferment, which was true. There was silence on the other end. I held my breath.

Then she said, “Oh ach du liebe (“Oh dear” in English) Danny, you are the wild one in the family.” She always called me Danny. She reluctantly agreed on the condition I pay her back and that if I failed in Steamboat I would go straight to Denver and register for school.

In the course of about three hours I transitioned from U.S. Ski Team member to pro ski racer, all because Bob Beattie put that ad in Ski Racing magazine. If I hadn’t seen that ad, this probably wouldn’t have happened.

Part Two

That night in Bend I went around and thanked my coaches and told them my intentions to turn pro. They were all very supportive and wished me luck. Then I went to the condo and sat around with the guys, drinking beer, talking about places we’ve been and people we’ve met. We were our own little band of brothers. We all had each other’s back. When they found out I didn’t have enough money for my bus ticket to Reno, they passed the hat and got me enough to get me there.

Early the next morning my good buddy Ken Corrock drove me to the bus station. We shook hands, he hugged me, wished me luck and I got on the bus to Reno, Reno to Salt Lake and then Salt Lake to Steamboat. I arrived in Steamboat on Wednesday afternoon, got signed up and was told my first round of qualifiers was Thursday morning. In pro racing you don’t get to the money round until you’re down to 16 racers, and there are over 100 skiers trying to make it to the group of 16. You have eliminations, and when you’re just starting out, you start at the bottom. Funny thing happened when I got to Steamboat: my skiing just clicked. I was on FIRE. The first round I had the fastest time. I had a Thursday afternoon qualifying and I won that race, too. People started to notice, including Beattie.

He came up to me after the second qualifying round and said that I was looking really good. I started to think this pro racing thing might just work. On Friday it gets tougher. It’s called the “Friday Afternoon Club.” At this point it was down to 50 skiers trying to qualify for those 16 spots. The 16 that move on join another 16 top seated skiers from previous races for Saturday morning qualifying. On Saturday and Sunday morning those 32 skiers race for a final 16 spots. If you make it through that you’re finally in the money round. I aced the Friday qualifying and “Oh, ach du liebe,” made the round of 16. I was in the money round after four qualifying races. I was skiing really, really well. All of a sudden, ski racing was fun again. I was hanging with my friend Tyler Palmer and everything was clicking.

Pro races consist of two events, a Giant Slalom on Saturday and a Slalom on Sunday. On Saturday in the Giant Slalom I made it to the quarter finals. On Sunday I did even better and made it all the way to the semi-finals. In two days, I made about $1,500. I went to Vail, Colorado the next week and made another $500.

Two thousand dollars in two weeks! I was in heaven, had done what I wanted to do, made a name for myself at the pro level and had momentum going into the next year. All the years I was on the ski team I skied on K2 brand skis, which I used in those two pro races. So, I felt my best chance for a sponsor the next year would be K2.

I paid my mom back the $300, never went back to college, ended up in the first lottery for the draft and got a high number—almost 300—which kept me out of the military. After the Vail race, Palmer and I decided to splurge. We flew to the Bahamas for two weeks—first class of course.

Part Three

The season was over, I had made a mark and was pumped for the next year. Solid finishes in the last two pro races gave me a good track record and a good chance at a sponsorship for the next year.

I went back to Squaw Valley for the summer. I had grown up there and had a lot of friends who were involved with ski racing. One was Warren Gibson, coach for the Squaw Valley junior ski team who had put together an amazing summer training program. I decided my best course of action was to stay in Squaw, concentrate on getting sponsored and work out with Gibson and his ski team, all of whom were in high school.

My idea of summer training was a little jogging, a little soccer, a few hikes and maybe work up a civilized sweat once in a while. Gibson had a completely different version of what summer training should be.

I had finally heard enough and politely interrupted him, saying, “What the f..., Gibson?! I want to make it to next winter. You have us riding 30 miles every morning, then we do a 5-mile run in the afternoon. Any sane person would call it a day after those two alone. But now you’re going to throw in the sprints and weight lifting. No one is going to do this under your ridiculous guidelines.”

tweet this

First, he got me into cycling. In 1972, cycling was not nearly as popular as it is today, so this was new for me. We found a really nice, used 10 speed and every morning at 7am we rode from Squaw Valley to Truckee High School. I learned about the Peloton (the group), slipstreaming, riding in a group, having your front tire inches from the person in front of your back tire, proper shifting of gears and riding hard, all out. When we got to Truckee, we would drop the ones that had school and ride back to Squaw, hard! This was about 30 miles round trip. Gibson considered this simply a morning warm-up. Around 2 in the afternoon, we would drive to Truckee High where Gibson made a deal with the school to use their universal weight machines. This consisted of 10 different stations where you would do a specific exercise. We would do 10 reps at each station.

But before we did weights, we did a 5-mile run, which allegedly was our “afternoon warm up.” Then we walked down to the football and track field where Gibson informed us that on Monday and Wednesday we would do weights and on Tuesday and Thursdays we would do sprints. Then he told us the sprints would consists of 10 440s (a 440 is a full lap around the track), to be followed by 10 220s (a half a lap around the track) with a 1-minute rest period between laps. If you didn’t complete your lap in the allotted time, you would do a bonus lap.

Well, I had finally heard enough and politely interrupted him, saying, “What the f..., Gibson?! I want to make it to next winter. You have us riding 30 miles every morning, then we do a 5-mile run in the afternoon. Any sane person would call it a day after those two alone. But now you’re going to throw in the sprints and weight lifting. No one is going to do this under your ridiculous guidelines.”

Gibson was a great and smart coach. After he heard my protest he blew his whistle and had everyone take five. He came jogging over to me, clipboard and all, and like a father who is about to have a serious talk with his son, put his arm over my shoulder and said, “walk with me.”

He starts out by saying, “Now listen, Moondog, I can see where you might think this is a little over the top, but I don’t just make this up. I did a lot of research on this and it’s a proven fact if you stick with this, you will be in the best shape of your life. Now I hear that Jean Claude Killy is going to join the pro tour this year, is that true?”

“That seems to be the rumor,” I answered.

Gibson then said, “Do you want to get in the starting gate against him and not be in the best physical condition possible?”

I said, “What, me race Killy head to head? That will never happen.” Gibson responded, “But what if it does? How many gold medals in the Winter Olympics, what was it, three?” Oh shit. Did he have me. So as I start doing my 10 440s and my 10 220s I came to realize you can describe his training philosophy with three letters: P, T, A—Pain, Torture and Agony. And just to put the icing on the cake, on Fridays we did both weights and sprints. Fridays became known as “Black Friday.”

Just to give you an idea, after each sprint we would collapse to the ground gasping for air and Gibson would blow his whistle and say “30 seconds!” Somehow we would get up, stagger to the start, then he would intone, “10 seconds… 5 seconds..” and we would do another 440. The pain was unreal. It was at this point I came to the conclusion it was going to be a long summer and fall.

Part Four

The first part of June I made a call to Gordy Eaton, director of racing for K2. I knew Eaton quite well and I thought this was going to be a relatively easy phone call. After exchanging the usual pleasantries, I went right into my spiel about why K2 should sponsor me. He listened politely and then explained that it was still too early in the year and no decision had been made, but he would be happy to throw my hat in the ring and to call back in July. I fell for his delaying tactics, hook-line and sinker, and agreed to call back in July.

Toward the middle of June I got a call from Bob Beattie asking if I could come to Aspen for three days to help with a promotion for the next year’s pro tour. He was getting all the Colorado TV and newspapers together for a press conference to unveil next year’s schedule and wanted as many racers there as he could get. I jumped at the opportunity, ANYTHING to get out of doing those damn sprints. Plus, I was honored that he even considered me.

I went to Aspen and my good buddy Tyler Palmer was there as well. I immediately started trying to convince him to come back to Squaw Valley with me, that I was working out with this lunatic coach who had an amazing program and he needed to get on board with me. Much to my joy he agreed to come back with me. When he got to Squaw and saw the enormity of the program, he, too, protested to Gibson. But Gibson had the gift of gab, and had Tyler on board in less than 5 minutes.

Meanwhile, I called K2 again in July and got the same answer. I was so desperate to get a contract, I didn’t want to believe I was getting the runaround. I called K2 in August and again in September with the same answer. Then it got interesting. Palmer was being managed by Bob Beattie and it was common knowledge that Rossignol was putting together a team of skiers from different countries. They needed an American, because the pro tour was an American invention, and we did all of our competitions in the U.S. and Canada. It was common knowledge that the American was going to be Tyler Palmer.

Around the middle of September it was announced that Jean Claude Killy was coming out of retirement and would be the captain of the Rossignol team. Knowing that Plamer was locked in with Rossignol, I didn’t approach them about sponsorship, still believing that K2 was my best bet.

By the first of October I had grown a backbone and called K2 and got them to come clean. With less than two months before the first race, I got hit with a bombshell: “The truth of the matter Dan, is that we have no intention of expanding our pro program. We have Spider and that’s who were going to run with. Our advice to you is to start looking for someone else besides K2 to be your sponsor.”

I was furious! If I had been told this in June I would have actually had time to find a sponsor. I felt like I had been kicked in the gut by a horse. I had no sponsor, the first race was around the corner and it was too late in the season to find one. After a couple days of some serious phone calls and brainstorming it became quite clear I was up a creek without a paddle. I had a couple of small offers, but nothing close to getting me through a season.

The first race was in 30 days. Can I possibly pull this off? I asked myself.

tweet this

Beattie had put together an impressive schedule running from Thanksgiving into April. It was beginning to look like I was going to have to go in as an independent and hope to have some good early results and to have some sponsor pick me up. A long shot, at best. I was extremely disappointed, frustrated, mad and hurt. It was like a dark cloud was over me and I couldn’t shake it. After weeks of desperately trying to put something together, I resigned myself to the fact that this is how it was going to be. I had lost all hope, had pursued every possibility, and then when you least expect it, out of nowhere the phone rings.

It was Bob Beattie calling for Palmer to tell him that Lange had come up with a much better offer than Rossignol—so he was killing the deal with Rossignol and moving forward on the Lange deal. When Tyler told me this, I looked at him with complete disbelief. “You’ve got to be shitting me!” I said. “This opens up a glimmer of hope for me. With you off the Rossignol deal, they have to replace you and it has to be an American, and only three people know about this, you, Beats, and me.” The first race was in 30 days. Can I possibly pull this off? I asked myself.

Without hesitation I phoned Rossignol. It was my lucky day. I got Director of Racing Gerarde Rubuox on the phone. I had met Rubuox once and introduced myself and he was nice enough to tell me he knew me. I didn’t waste any time and explained to him how I’ve been trying to get a sponsor and that Palmer has just signed with Lange—which meant he needed an American to fill that spot.

“With three weeks till the first race, I am calling to let you know, I’m your guy,” There was a long silence and then he said, “No, Tyler is skiing for us.” I said, (Au contraire, mon ami) in about 15 minutes you’re going to find out what I just told you is true.” He said, “OK, this is all news to me, let me make a few phone calls and I will call you back in half an hour.”

I hung up. Palmer asked, “Well what’d he say, what’d he say?” I replied, “He said he will call me back in half an hour.” Sure enough, in half an hour the phone rang. “Hello Dan, this is Gerarde, it seems your information is correct. Yes, at this time we are going to have to replace Tyler with another American. Is that American you? I can’t say yes or no. The first race is in three weeks; we need to find someone soon. I will certainly put you in for consideration, but I must consult with some other people before I make a final decision. Today is Thursday, I will call you back on Monday afternoon with my decision.”

"If you place third or better in the first two races, we will award you a full contract. If you don’t, you’re on your own.” Gerarde Rubuox

tweet this

I said, “OK, talk to you on Monday,” and hung up. Then I realized, Monday, shit, that’s four days from now. I’ve got to wait four days before I find out. This is going to be the longest four days of my life. And they were. I drove Palmer crazy coming up with every possible scenario that I thought Rossignol could come up with. Finally, on Monday, Rubuox called me. The conversation went something like this:

“We know about your strong finishes last spring. You were on the U.S. Ski Team for a couple of years. So, you have talent, but how much talent? Can you maintain top three finishes throughout an entire season, or are you a one-hit wonder? Do well in one race, then take your contract money and fade away? You’re the first one to approach us, so, with only three weeks until the first race, this is what we will do. The team is in Vail now training. We will send you to Vail, pay your expenses. You will stay with the team and train with the team. We will provide you with equipment. We will pay for all your expenses through the first two races. If you place third or better in the first two races, we will award you a full contract. If you don’t, you’re on your own.”

I sat in stunned silence, trying to make sense of it all. The bottom line was, this was as good as it was going to get. I had no choice. If I don’t take this, I have nothing. So, with all the confidence of having no other options, I said, “OK Gerarde, you’ve got a deal, third or better.” He said, “Fine. I am going to put you on with my secretary and she will make your travel arrangements.” When I hung up Palmer asked, “What’s going on, what’s going on?” I told him, “I just made a deal with the devil, and I’m going to Vail.”

That was the end of our summer and fall in Squaw Valley, and a couple of things stick in my head. If I hadn’t run into Tyler in Aspen, I wouldn’t have been with him when he found out about the Lange deal. I believe the reason Rossignol offered me a shot was because of my timing, as I was on the phone to Rubuox even before he knew about it. And, son of a buck, Warren Gibson was right. By the time we left for Colorado we were in the best shape of our lives. We could ride bikes all day, run long distance all day, run sprints all day, push weights all day and not be tired. If you read this, Gibson (Hoot), thanks. You were right and you helped get us there, I will never forget running 440s in the dark, with our cars up on the track with the lights on so we could see where we were going. Great, great stuff.

Part Five

I found myself in Vail, Colorado, plucked by Rossignol from the depths of despair and given a breath a new life. I found myself in the company of Jean Claude Killy, Alain Penz, Pierre Poutenobole, all from France, Otto Tschudi from Norway, Malcolm Milne from Australia and myself. Killy came up to me and introduced himself, as he had been apprised of my status. I knew Tschudi pretty well, but no one else. For two weeks we trained. I tried to stay out of the way and keep a low profile. Oh, man, was I nervous, but I hung in there and by the time we left for Aspen for the first race I was feeling pretty good.

This was it. Sunday morning. I could feel the pressure before I even got out of bed.

tweet this

Finally, it was time. The first race of the year. Giant Slalom was on Saturday; Slalom on Sunday. I had two chances and had to make at least the semi-finals to get third. It wasn’t going to be easy. There were a lot of good skiers there. So, I had no problem making it into the round of 16. In my first heat I walked out of my binding and disqualified. One chance gone, three to go. The next day in the Slalom I qualified but fell in the first round. Ugh, I couldn’t afford mistakes. Aspen was a bust and I left frustrated but not defeated. I was skiing well and just needed a few breaks to go my way. The next week, on Saturday in Vail, I didn’t get one and skied out of the course in the round of 16. I had one chance left, the Slalom on Sunday, and Slalom was not my event.

This was it. Sunday morning. I could feel the pressure before I even got out of bed. I kept saying to myself, “You can’t make mistakes today, you have to ski perfect, you have to go after it, you have to concentrate.” So, I made it through the morning qualifying and into the round of 16. I can’t remember who I skied against in the round of 16, but I beat him and was now in the round of eight; the quarter finals. Still not home free. I can’t remember who I raced against in the quarter finals, but I skied good, made no mistakes, concentrated and won. I was in the semi-finals with four racers left: myself, Tyler Palmer, Spider Sabich and Jean Claude Killy. I was matched against Palmer; Spider against Killy. The losers go on to race for third and fourth place, the winners go on to the finals and race for first and second. Palmer, a slalom specialist, had won a World Cup slalom in Kitzbuhel, Austria earlier that year. He grew up in New Hampshire where all they do is practice Slalom on boiler plate ice. I skied well but he took me and moved on to the finals.

I was either going to race Sabich or Killy for third or fourth place. I watched Sabich and Killy go at it in their semi-final round, and lo and behold, Spider Sabich beat Jean Claude Killy. Third place was now not a gimme. I was going to have to race the greatest ski racer in the history of the sport up to that time, who had won three gold medals in the Olympics—the Muhammad Ali of ski racing. When I was in high school, he was my idol. Not only that, I was going to get one chance, and one chance only, and Slalom was not my strong event.

I slowly started to make my way to the lift for the ride to the start. As the chair came around and I was just about to sit down, out of nowhere came Tyler, sitting down next to me. We headed up the hill. He said, “Moon Dog, listen to me carefully because I’m only going to have time to say this once. This is the race you’ve been waiting all your life for. You can beat him. He doesn’t know who you are. He doesn’t know you ran 10 million 440s this summer. You can surprise him. You can do this. This is your moment. This is your race. He is in your house. You need to beat him out of the start, go into the first jump ahead of him or neck and neck. You do that, and you’ve got a shot at the deal.” He made me a believer.

The start was quite a scene. Reps, coaches, racers who had been eliminated and officials were all at the start. No one wanted to miss this. There were 5,000 people along the course and in the finish area. Beattie had loudspeakers set up along the course and he was announcing, and he was good at working up a crowd. It was time. The start has two horse-race-like starting gates 12 feet apart. Racers step into a box-like structure and the gates open simultaneously. I stepped into the start with the worst case of butterflies in the history of mankind. Beattie was working the crowd.

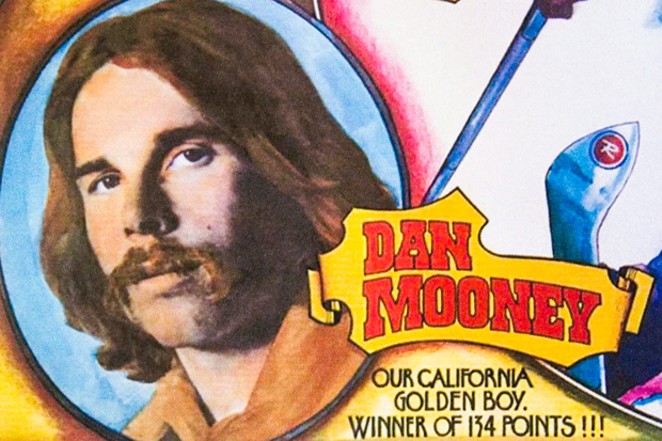

“Ladies and gentlemen, let me set the stage for the upcoming semi-final race for third and fourth place. On the blue course, from Squaw Valley, California, straight off the U.S. Ski Team, racing his first full year on the pro tour is 21-year-old Dan “Moondog” Mooney. In the red course, from Val D’isere, France, is triple Olympic gold medal winner Jean Claude Killy. What must be going through young Dan Mooney’s mind as he steps in the start to race Jean Claude Killy, three gold medals in the Olympics. That’s not all, if Mooney beats Killy here, Rossignol is prepared to give the Moon Dog a full contract. Fourth place he stays independent. Talk about pressure. OK, the courses are clear and the racers are ready.”

When that gate opened, I shot out like a cannon, getting an early lead. First gate, second, then third. I could feel his presence right on me. We hit the first jump side by side and as we made our way to the second jump, he took a slight lead. We hit the second jump and we both sprinted to the finish. He took the first run by 2/10ths of a second—not a huge lead. Going back up the lift, Palmer was pumping me big time. “See, he’s not so bad, he’s not so bad. Two-tenths of a second, you’ve got him! He’s nervous, he didn’t expect you to be so close! Nail him out of the start again, get to the first jump, and turn on the afterburners.”

For the second run we switched courses, and as I moved into the starting gate and we were getting ready, I was pounding my ski poles in the snow and taking deep breaths. I looked over at Killy. To my surprise, he was just standing there looking at me, so I stopped what I was doing and stared back at him. This went on for about 15 seconds—and call me crazy—but I swear I saw fear in his eyes. At that moment I said in a real loud voice so everyone could hear me, “OK, let’s do this!” I think the starter may have been quietly rooting for me, because he then says, “Mr. Mooney has indicated he would like to proceed with the second run, do we have a clear course? Racers ready?”

When those gates opened, it was game on and clear that Killy had no intention of me beating him. And me? Well, I had something to prove. We raced like two men possessed, hitting gates, taking chances. We hit the first jump neck and neck. As we made our way through the middle of the course it was more of a slug fest than a ski race. As we approached the second jump Killy faltered slightly and I was able to make a move on him and I took a slight lead. As we got to the second jump, I increased my lead to about half a ski length, just enough so I could no longer see him in my line of sight. I landed off the second jump and I just focused on the finish, five gates to go. I put everything I had into it and then some. I crossed the finish line, looked over my shoulder to see where he was. No Killy. I came to a stop. The finish area was eerily quiet and Beattie wasn’t saying anything on the PA. I looked up the hill and there between the second jump and the finish was Killy, standing on the hill, putting his ski on.

Then Beattie comes on the PA: “Ladies and gentlemen, I have the official ruling from the Chief of Course, Jean Claude Killy landed wide off the second jump, hooked a tip, and missed a gate, officially disqualifying. Mooney takes third! Mooney takes third! The Moondog has done it, he has upset Killy and taken third place!” I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. Palmer was the first one to me. He wrapped his arms around me and slapped me on my back. “You did it Moondog, you f...ing did it! You pulled it off! You f...ing pulled it off! You son of a bitch! When did you become a Slalom skier?!”

A crowd gathered around me. I had press and TV people asking me all these questions. How did I do it? What was my strategy? I was really speechless. Then working his way through the crowd coming towards me was Jean Claude Killy. As he approached me, people stepped aside to give him room. He came right up to me, put out his hand to shake mine, and said, “Congratulations Dan, today you skied like a true champion. You deserved to win, welcome to the team.” I think I said thank you, or at least lipped it. And with that he left the finish area. I looked at Palmer and said, “He said welcome to the team didn’t he?” Tyler goes, “Yes indeed Moon Dog, that’s exactly what he said. You just got endorsed by the man himself. Way to go.”

So, I took a deep breath, picked up the pen and as I signed my name I had only one thought, “Moondog, you’re going to the show.”

tweet this

After the podium Gerarde Rubuox came up to me and said, “Meet me at my hotel room around 5.” So at 5 pm, I knocked on his door. He welcomed me in and had me sit down. Then he handed me a contract and says, “Read this over and if you’re in agreement then sign it.”

On it, it says, “Rossignol Ski Company is to pay Dan Mooney $15,000 to race on the ‘72-‘73 world pro ski tour. Rossignol will pay all travel expenses, will provide all equipment and clothing…” As I was reading this, I couldn’t help but to flash back to the condo in Bend where this whole crazy roller coaster ride began, and the confluence of events that had to occur for me to get me to this moment. I just kind of started shaking my head. Then Rubuox said, “Is there a problem, you are shaking your head?” “Oh, no, no, there is no problem, I was just thinking… oh never mind, Gerarde, there is no problem at all…”

So, I took a deep breath, picked up the pen and as I signed my name I had only one thought, “Moondog, you’re going to the show.”

The End.

It has come to my attention an explanation is needed. Going to the show is a phrase that comes from Major League Baseball. When a minor league player is called up to join a major league team, he is typically called into the manager’s office, told to clean out his locker and then told congratulations your going to the show. He’s going to play in the majors. It’s a statement that transcends all sports, including ski racing.

Dedicated to the memory of Bob Beattie.