Central Oregon's population has grown massively in the last three decades, transforming Bend from a small lumber town into one of the fastest-growing cities in the United States. Its humble beginnings and quick growth contrasts the numerous settlements that formed concurrently near the turn of the century, but became abandoned over the years—some still standing as ghost towns sprinkled across the desert landscape.

Many of these towns were vacated as quickly as they grew. Some held on in some form for decades and others remain, memorializing the spirit of the first homesteaders claiming their 160 acres.

But what killed these communities in an area where other towns are now thriving?

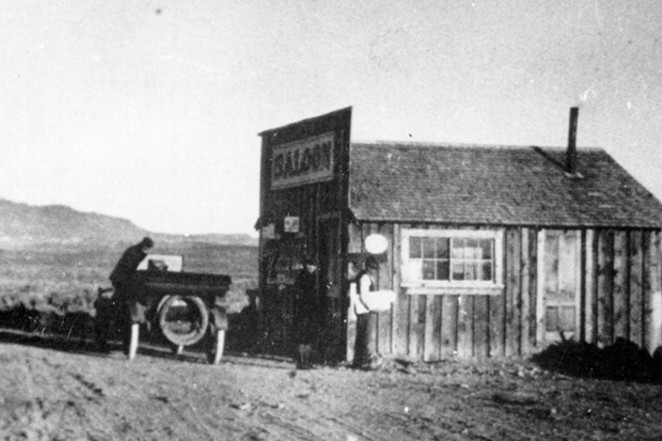

Richmond: Sheep and Rebels

Twenty miles north of Mitchell, past the Painted Hills, the bones of a town lie scattered among newer-built cattle ranches. A store, church and school are split by a modern asphalt road. The town of Richmond was created when traveling in the area was extremely difficult. The settlers were nearly all sheep herders who grazed their flocks on the remote mountains during warm months and moved to valleys when it got cold."They just got tired of having to haul all their stuff in from Fossil or Condon or Prineville or John Day, and they wanted to have their own community where they could sell and buy things," said Steve Lent, a historian at the Bowman Museum in Prineville.

Among the pioneers who settled in Richmond in the late 19th century was R.N. Donnelly, an Oregon state senator who led the effort for the establishment of Wheeler County. The town was named after the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia, after many arguments between Donnelly and settler William Water, whom Donnelly called a "rebel," about what the town should be called.'

The town was a hub for the newly established county. A meeting of the Wheeler County Pioneer Association in 1901 drew more than 450 people to the small town. Though promising at the turn of the century, Richmond would be irreparably damaged by the decline of the sheep industry and the advent of cars.

For years there was strife between sheep herders and cattle ranchers, resulting in the Sheepshooters' War and over 25,000 sheep slaughtered by paramilitary sheepshooting associations between 1895 and 1906.

"People don't realize how many sheep were in this country. That's actually what led to the conflict between the sheep and cattlemen," Lent said. "Cattlemen said the sheep ate up all our grazing land and no self-respectable cow would eat the same grass after a sheep."

The town and sheep herders would survive the war, but not for long. The herders were running massive flocks of sheep and relied on grazing on public lands to support them.

"They really counted on having their unlimited summer grazing up in the forested areas, and when they put allocations on it, limited the size of the herds they could have, it just wasn't as profitable," Lent said. "Most of the sheepmen moved to cattle, but that that just led to the demise of Richmond because that was their livelihood."

The town also declined as shipments became timelier due to cars and roads improving in the early 20th century. Wagons typically need to stop every 15 miles or so, but cars could go nearly 100 miles before needing service.

People started moving away from Richmond in the late 1920s and it would be mostly empty by the 1930s. A few stragglers would remain. The post office, usually the last thing to go in a town, Lent says, was closed in 1952.

"When they left, they just left everything. That's why it was a ghost town," Lent said. "All the buildings were there, but most of the people were gone by the late '20s, early '30s."

The town's rise and fall mirrors other settlements of people seeking opportunities out West—but other towns didn't die out so easily.

Millican: One-Stop Shop, One-Man Town

Much like Richmond, Millican in the late 19th century began attracting those interested in trading livestock. George Millican, the town's namesake, was the most prominent cattle rancher in the area when the post office was established. Cattle was the original industry, but settlers moved in under the Homestead Act, spurred on by railroad propaganda hyping the land's fertility, and by the turn of the century many farmed dry land wheat.Farmers usually didn't make enough money on their crops alone, and the patriarch of the family often worked a job while the family maintained the homestead. The town was never the regional hub that Richmond was, but at its height had a population of around 60 and even established a school between 1913 and 1916. Shortly afterwards, though, many of the homesteaders would leave.

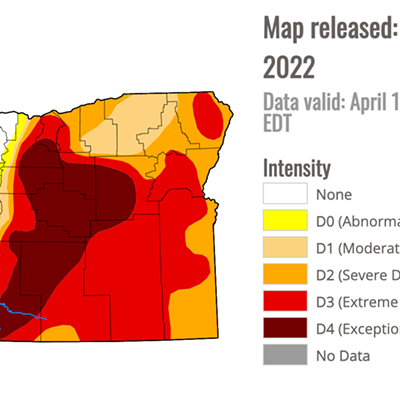

"When they first came were kind of wet years," Lent said. "We had several years of drought, and particularly out on the desert like Millican and those areas, the homesteaders had a tough existence anyway. Most of it was dry land wheat, and when they didn't get any winter moisture they couldn't make a living off of it, so they either abandoned or sold off to larger landowners and left."

By 1920 the population was whittled down to one. But unlike Richmond, Millican would live on as a peculiar single-family town for nearly 70 years. As the population was dwindling, the Millican store was bought by William "Billy" Rahn, who delighted in being the sole resident of the town. During his ownership of the store from 1920 to 1945, Rahn would appoint himself mayor, secretary of the chamber of commerce, chief of police and chief air raid warden, along with his duties as a postmaster and storekeeper.

In 1940 Rahn achieved national celebrity after being featured on Ripley's Believe It or Not as both a cartoon circulated in print and on their nationally syndicated radio show. Rahn told The Bend Bulletin in 1942 that he received hundreds of letters from fans in the months after being featured in Ripley's, and was later invited onto the national radio show We The People where he boasted of the town's ability to blackout in two seconds in case of an air raid.

"The Millican record of two seconds is due to two things," Rahn said. "One is that nobody is ever more than two seconds away from the main switch and the other is that I am the entire population of the city."

He said if the sage hens and jackrabbits get out of the way then he could evacuate the entire city to a safety zone in less than a minute and a half.

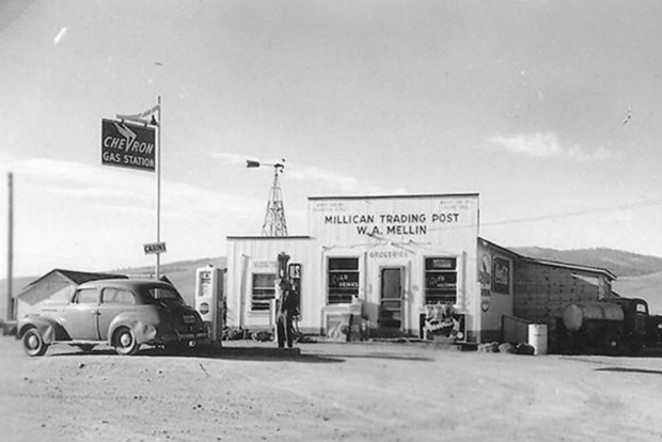

Rahn sold the town in 1945, after passing the 70-year age limit that existed for postmasters at the time. It would briefly be run by George Petry before it was sold to its next longtime owner Bill Mellin. Mellin would manage the store for over 40 years, much of that time with his family helping him.

Mellin was well liked among the ranchers, hunters and travelers who stopped in his store. Many would stop by just to chat or play cribbage, and at night Mellin would leave 8 to 10 gallons of gas in the pump in case someone needed it after hours.

The first 20 years manning the Millican store went well for the Mellins. Though they weren't getting rich running it, they made enough to live comfortably and support their family. That would change in the '70s, when a series of tragedies would whittle the town's population back down to zero.

In 1971 Mellin's daughter was killed by a drunk driver. A few years later his wife would die from a heart attack and in 1980 his son, a pilot, died in a plane crash. Mellin considered selling but was reluctant and priced the property three times its assessed value. Mellin would never sell, and in 1988 he was shot in the back of the head by David Wareham, who briefly worked at the store after a stint in prison.

After Mellin's murder Millican never returned with the consistency of its two prior owners. The town was again sold in 1991 to the Haisler family, but they faced financial trouble almost immediately. By 1997 they were facing foreculsure, and the new owners, the Resnicks, hoped to transform the property into an animal shelter—a dream that never came to fruition.

Bruce Resnick leased the store to the Murray family in 2002, and they managed it for the next three years. It was the last time the Millican store was open for business. The town was again sold in 2010 to Leonard Peverieri, who hoped to cash in on the only commercially zoned property between Bend and Brothers, but it didn't work out. In 2017 he put the town up for sale at the price of $1.5 million, a price nobody has been willing to pay yet.

Brothers: The Pioneer Town That Could

The town of Brothers has similar origins to the other towns that popped up during the homesteading boom, but unlike Millican and Richmond, Brothers is not a ghost town. The population is around 60, about the same as when it was settled in the early 20th century by sheepherding families. The Brother's Stage Shop is still openmore than 100 years, and the small schoolhouse across the street still teaches about a dozen kids from nearby ranches.

Like Millican, the town survived as one of a few stations on the route between Bend to Burns.

"Millican lasted quite a while mostly because at the time there were a long ways between Bend and Burns," Historian Steve Lent said. "That's why Millican and Brothers even got established, to provide a place for people to get fuel."

The Millican and Brothers stores were built when wagon travel necessitated stations nearly every 15 miles. Now, between Burns and Bend the only station providing gas is in Hampton at the eastern edge of the high desert.

"As cars and roads improved, there wasn't that need," Lent said. "Back then a car might make 70-100 miles on a tank of gas."

The Brothers store wears its heritage on its sleeve, with the shop's walls covered in the history of the area—scouted by legendary frontiersmen such as Daniel Boone, Kit Carson, Peter Ogden and homesteaded by vaudeville star Klondike Kate. The wagon outside the shop and the history on its walls connect the land to a pioneer past that is becoming more and more rare, but is still evident from the abandoned buildings that outlasted their residents.