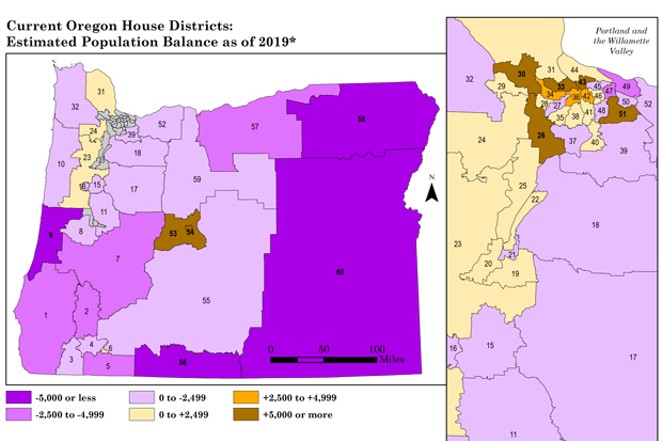

Against the backdrop of Census data delays and a packed legislative session, Oregon lawmakers are embarking on the once-a-decade process of "redistricting," in which they redraw the lines for state House and Senate districts, along with the U.S. Congressional Districts based on shifts in population.

In order to evenly distribute the population, each Oregon Senate district will need to be around 138,00 people and each House district will need around 69,000 people. Central Oregon's districts are far over those marks and will need to shed numbers. But while experts predict that these districts will shrink, they will likely stay true to shape.

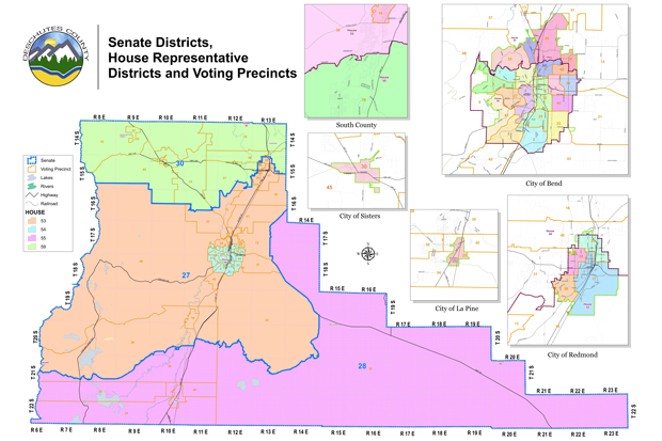

Central Oregon's House districts are known as the "donut" and "donut hole." House District 53, or the donut, makes up much of Deschutes County, including the more conservative-leaning regions of Redmond, Sunriver, Tumalo and Deschutes River Woods. District 54, otherwise known as the donut hole, was carved out of District 53 and includes most of the more liberal-leaning Bend, the county's population center. These two districts make up Oregon's Senate District 27.

In the past 10 years, according to estimates from the American Community Survey, Bend's District 54 has seen a population increase of nearly 15,000 people, growing from 63,563 to 78,480 residents. The surrounding District 53 has also seen significant growth with an increase of almost 10,000 people, rising from 64,805 to 74,480 residents.

These districts have looked like a donut since the 1990s but have shrunk as the population has grown. Judy Stiegler, a political science professor at OSU-Cascades, represented Bend's District 54 from 2009 to 2011.

"(District 54 has) shrunk in size geographically, but the population base has stayed the same," said Stiegler, who refers to herself as the "one-term wonder." Until Rep. Jason Kropf (D-Bend) flipped the seat this year, Stiegler had been the only Democrat to represent District 54 since 2011, even though the number of registered Democrats in the district has been steadily rising.

House District 53, currently represented by Rep. Jack Zika (R-Redmond), has consistently gone to Republicans for the last 20 years, along with Senate District 27, now represented by Sen. Tim Knopp (R-Bend). In 2020, Knopp barely gained 50% of the vote though, since Senate District 27 has become increasingly competitive for Democrats with the growing progressive faction in Bend—largely in District 54.

If District 54 continues to shrink and shed the more rural areas on the outskirts of Bend, this could mean more wins for Democrats. But Stiegler said the high number of non-affiliated voters in District 54 will continue to make it a swing district.

"I don't think you're ever going to see (District 54) as a solid one way or the other," she said.

Revisiting an Old Debate

In the past, Oregonians—mostly Republicans—have advocated to get rid of the donut-like lines altogether. They hope to return the districts to how they were before the 1990s: dividing the region down Highway 97 into east and west districts.

This proposal was at the forefront of debates in 2011, but according to Stiegler, "People argued very hard and loud that by dividing Bend by east and west, what you were doing was basically dividing a city that didn't need to be divided." Instead of splitting the region east and west, lawmakers ended up further tightening the donut hole around Bend population centers.

Regardless, former Secretary of State Bev Clarno, a Redmond resident who held the office from 2019 until this year after many years as a state lawmaker, has long advocated for the east-west split so both Districts 53 and 54 have urban and rural areas.

"I think it's a big mistake to just make a donut hole," she said. "I think (District 54) should include rural parts of our community so that our representative is representing all interests of Central Oregon."

Opponents of this proposition argue an east-west split would tilt the districts toward conservatives and would divide Bend, which they consider a "community of interest." Even Clarno doubts there will be any substantial push for this proposition this year.

"I don't think anybody's pushing that but me, and I don't have any control over it," she admitted.

According to Oregon statute, districts cannot divide communities of interest, which is interpreted as cities or ethnic groups. Districts also must be contiguous, be of equal population, utilize existing geographic or political boundaries and be connected by transportation links.

Where politics come into play

Oregon law attempts to prevent gerrymandering, saying, "No district shall be drawn for the purpose of favoring any political party, incumbent legislator or other person." Still, Clarno said parties will always draw boundaries to their benefit and has long argued that an independent, nonpartisan commission—created by the legislature—should draw the lines. This is different from the commission the newly elected secretary of state, Democrat Shemia Fagan, has advocated for, which would be created by her office, rather than the legislature.

Redistricting could be ultimately turned over to Fagan if lawmakers fail to successfully pass new legislative boundaries by Sept. 27, the extended deadline the Oregon Supreme Court agreed to in order to account for U.S. Census data delays. Prior to that, the redistricting deadline was July 1, even though the U.S. Census Bureau will not release data until mid-to-late August because of pandemic-related delays.

“Please don’t draw the districts in a way that shortchanges both the urban interests of Bend and the people that live here, and the rural interests of the communities that surround us.”—Melanie Kebler

tweet this

Both lawmakers and Fagan were relieved that they were granted the extension and that redistricting will be complete in time for 2022 elections.

"It was a victory for the legislature and for the (Oregon) Constitution," said Knopp, who sits on the Senate Committee on Redistricting.

Fagan also said in a statement, "Our agency's core objectives were to prevent moving the 2022 election dates and to preserve robust public input by starting the process with available population data. We appreciate that the Oregon Supreme Court thoughtfully adopted both of our objectives."

State Democrats also recently reached a bargain with Republicans to essentially grant them veto power over legislative and congressional maps. In exchange, Republicans agreed to end delay tactics that were slowing the legislative session.

Some people argue this power-sharing could result in gridlock. But, Knopp has faith the legislature can successfully draw the lines.

"I think that committee has been working well together, and that we all want to have a legislative plan that is adopted, and we're looking toward that," Knopp said. "So, I do feel hopeful that we can get that done."

Oregon's legislature doesn't exactly have a great track record of drawing the maps. The 2011 redistricting was the first time in decades that lawmakers successfully passed maps without a veto from the governor or court challenges that landed the job with the secretary of state.

Still, Knopp argues the legislators will be able to draw the maps without letting political partisanship get in the way.

"As I say, the data is the data, and that's going to direct what we're able to do," he said. "Some people will like certain parts of it, and some people won't."

Gaining public input

In a typical redistricting year, lawmakers travel to each of Oregon's congressional districts and hold public hearings. But, because of the pandemic, those have all been held virtually. Knopp hopes to hold hearings in-person in the summer, if the pandemic allows.

"It would be helpful for legislators to go see communities, especially those where there's going to be significant changes in the lines," he said.

So far, Knopp has heard from Central Oregon residents that they want to keep Bend and urban areas together in a district, maintaining the donut and donut hole.

Melanie Kebler, one of Bend's newly elected progressive city councilors, virtually testified in her own capacity on March 20. She argued that lawmakers should continue to consider Bend as a "community of interest" and keep it united.

"It's time to fully take into account the changes that have happened in Bend over the years and respond to our need for strong representation on our city's issues and interests in Salem," Kebler said in her testimony. She continued, "Please don't draw the districts in a way that shortchanges both the urban interests of Bend and the people that live here, and the rural interests of the communities that surround us."

Peter Kunen, another Bend resident, also testified in favor of the donut hole, arguing that Bend has "unique urban interests" that differ from the nearby rural areas.

In addition to cities, ethnic groups are considered as communities of interest. Joanne Mina, volunteer coordinator at the Latino Community Association, pushed the committee to keep Central Oregon's Latinx residents united as much as possible, so as to not divide the community's voice.

"Historically the process of redistricting has been used to disempower communities of color," Mina said. "Oregon's legislature must make it clear that marginalized communities must help drive this process and demonstrate that, in Oregon, democracy and justice are for all."

Coalitions such as We Draw Oregon, led by BIPOC and LGBTQ+ organizations, have mobilized statewide to center equity in the redistricting process and encourage communities of color to get involved.

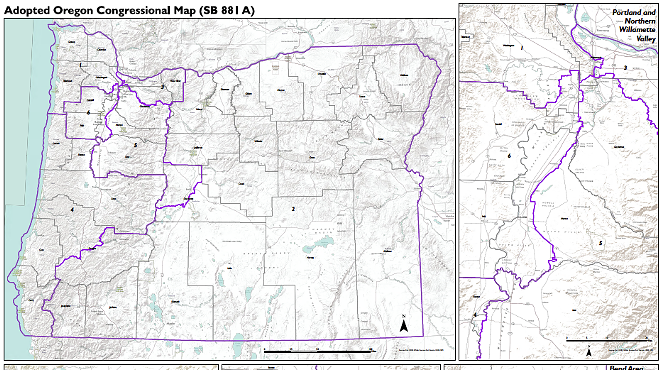

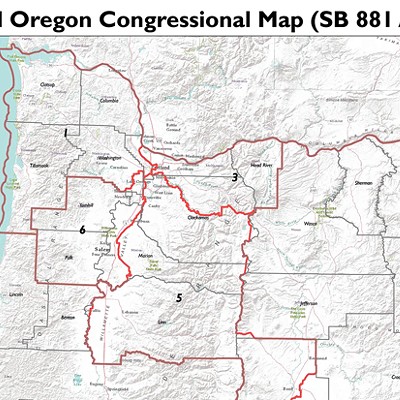

A lot is on the line for Oregon this year. The state currently has five seats in the U.S. House and is expected to get another one due to the state's population growth relative to other states. The U.S. Census Bureau has said it will release its first round of data later this month, which will start to determine which states will gain seats and which will lose them.

Stiegler, the political science professor, predicts the greatest battle in Oregon to be over the congressional lines, if the state gets another seat. The new district could be carved out in a growth area, like the Willamette Valley or the Portland Metro area. If the legislature fails to pass maps for congressional districts, the job will be turned over to the courts.

Stiegler encouraged Central Oregonians to "sit up and take notice because it can impact you directly," she said. "It can determine who's representing you."

More public hearings may be held once the state starts receiving census data and drafting maps. Dates of these hearings have yet to be determined. More information about redistricting in Oregon can be found at oregonlegislature.gov/redistricting/.

By the Numbers:

House District 53

2010: 64,805 people

2019: 74,252 people*

House District 54

2010: 63,563 people

2019: 78,480 people*

*2019 estimates from the American Community Survey