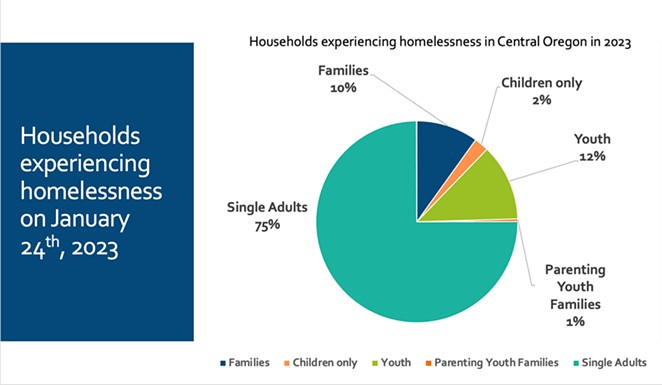

Central Oregon's Homeless Leadership Coalition counted 1,647 people experiencing homelessness on a single night in its 2023 Point in Time Count, a 28% increase from 2022. Nearly 200 of the survey's respondents were under 18 years old, and another 133 were between 18 and 24 years old and considered "unaccompanied youth." But Bend-La Pine Schools has twice as many students reporting they are homeless than was reported in the PiTC, which covers Deschutes, Jefferson and Crook counties.

The HLC acknowledges the Point in Time Count is flawed. For one, it's considered to be only a snapshot of the homeless population. People can also slip through the cracks and avoid being counted if they aren't found by service providers or don't cooperate in a survey. The count also doesn't factor in the way most children experience homelessness — which tends to involve staying with friends or family rather than checking into a shelter or living on the street.

"I just had a really hard life with parents, and financially we were struggling. Things just didn't really work out in my or my parents' favors," said local youth Isabelle Patterson. "And eventually it gets to a certain point where people just start giving up on themselves. So, I had to take a different route, because I didn't want to be in that same position that I was in for a while."

Patterson is in a program at the Cascade Youth and Family Center, which is part of the broader J Bar J network of services for kids and youth. She spent two years living with friends before enlisting in the program. Now, she's getting shelter as well as life advice.

"They help financially. They just helped me get my life together, they helped me get myself into college and try pushing me into the right directions because many kids my age have their parents still do that, not by themselves. And so, this program is just based on independence," Patterson said.

She's been with CYFC for almost a year and a half and is in the Youth Advisory Program, a group of kids who provide feedback to staff, advise peers and provide help for her cohorts. Her goals after the program are to find a place to live, enlist in the Army Reserve and get a degree in health sciences for a nursing career.

The needs of homeless children and teens

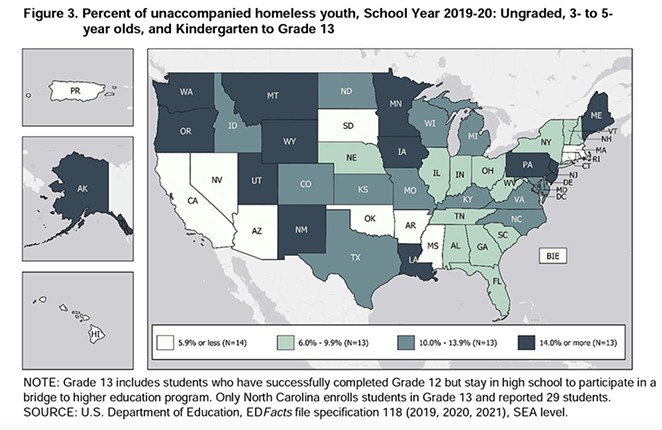

Eliza Wilson, the director of runaway and homeless youth programs at the CYFC and the chair for the Homeless Leadership Connection, said children need a specialized form of care that may not apply to adult populations. Wilson said the true number of kids without a home may be even higher than what's identified through any available measurements because kids experiencing homelessness are less likely to go to school, and families are warier of interacting with service providers.

"It's true that youths are underrepresented in the Point in Time Count and that's just always been the case," Wilson said. "They may feel that they have greater risk factors for accessing support, like worrying about getting their families in trouble, or worrying about going into the foster care system. And families worry about their children being removed."

Wilson, who herself was an unaccompanied youth, has been working with J Bar J for 14 years and has seen many ways kids experience homelessness. Sometimes kids experiencing neglect or abuse at home may find more safety and stability outside of it. A death in the family may plunge a kid into the home of a relative or parent who previously wasn't involved in their life. Low-earning families may just be unable to care for their kids. Wilson said a plurality of unaccompanied youth, over 40%, are LGBTQ and many of them were kicked out of their homes by unaccepting parents.

"I would say [the number of LGBTQ-identified homeless youth] hasn't really changed since I've been involved in J Bar J," Wilson said.

CYFC's programs range from street outreach, where supplies are given to people where they're at, to long-term shelters that house kids for up to two years. Between that there's family mediation to resolve family conflicts and a three-week emergency shelter. The organization, though, doesn't always have the capacity to meet their clients' needs.

"We can always serve youth with crisis response, but if our shelters are full, which a lot of times, like right now, they are, we have more youth there than we have beds sometimes," Wilson said. "We have to kind of be strategic about growing capacity; we can only serve a certain number of youths in the buildings."

CYFC has two long-term shelters: The Loft, which can host people for up to two years, and Grandma's House, which specializes in pregnant girls and young mothers. Some kids are placed with host families who act as foster families, but without a child being designated as a ward of the state. CYFC can train and compensate hosts, but Wilson said they're currently short on host homes and are seeking more people to get involved.

The frequent and intense needs of youth services is expensive, but Wilson sees it as a preventative measure. Homeless children are more likely to become homeless adults, according to the National Conference of State Legislators.

"We're doing daily check-ins, we're working with them intensively, if we are able to do that, even if we do it for a short time, then we're deducing the likelihood that they'll be the chronically homeless with a long life of trauma, because homelessness is very traumatic for the individual that's experiencing it," Wilson said.

In the schools

The McKinney-Vento Act guarantees kids experiencing homelessness the same right to public education as other students. That can be easier said than done, though. Homeless students may not be able to readily provide an address, immunization records or birth certificates to schools — items that are normally required when enrolling in school.

"My primary focus is protecting the educational rights of students who are experiencing homelessness. And so, the first thing we want to do is if a student is new to our area, and they qualify under McKinney-Vento eligibility, then we want to get kids enrolled as quickly as possible," said Sandy Schmidt, the McKinny-Vento liaison for Bend-La Pine Schools.

In 2023 BLS identified 438 students eligible for McKinney-Vento support, 128 of whom are unaccompanied. About 70% of those students are "doubled up," meaning they're living with another family based on an informal agreement.

"The doubled-up situations can be our most unstable, because any time that host family can say, this isn't working out. And more often than not, there's inadequate space. So, we may have a family in a garage, or their storage shelter out back, or maybe there's 10 people in a two-bedroom apartment," Schmidt said.

The other primary function of a McKinney-Vento liaisons is arranging transportation. Unsheltered kids may be more mobile than their sheltered peers, and if they're camping could be subject to sweeps and code violations that keep them on the move. The school district still must find ways to get kids to school, even if they move across town. It can even mean working with kids as far away as Madras or Prineville, which sometimes happens when families find more affordable options for long-term housing.

"We don't want to make that child move midway through the school year, so they're eligible for transportation to remain at their school of origin for the remainder of the school year, because we know every time kids have to move schools, then they lose ground educationally," Schmidt said. "Working with unhoused people that grew up experiencing homelessness as a child, they'll tell me, 'I went to 12 schools, 17 schools.' It's a really common issue, and a barrier to being successful."

About 70% of McKinney-Vento-eligible students are consider chronically absent, meaning they missed 10% or more of their school days. About half of McKinney-Vento students graduate compared to 85% of all students in the Bend-La Pine district. Lower achievement in schools can feed into the cycle of homelessness from childhood to adulthood.

"Education is the number-one factor for preventing future homelessness that we know of, if you're focusing on young adults or children. Young adults without a high school diploma or GED are four and a half times as likely as their high-school-educated peers to experience homelessness as a young adult," Schmidt said. "We know that if we can help kids get to school, stay in school, hopefully get something post high school, then that's the ladder to a living wage job."

Isabelle Patterson, the young woman in the CYFC program, said she started high school during COVID and did well under distanced learning. When in-person learning resumed, though, it wasn't easy going back to school.

"I just couldn't handle being around people who had no idea what I was going through," she said. "I feel like I was doing stuff to help myself, but in ways that most people wouldn't understand."

Now that she's on track to graduate, and has plans for her next steps into young adulthood, she's got a sense of self-determination and confidence in her future.

"I would just say that it doesn't matter where you are in life, you always have that choice to make it your life or continue to fight through it," Patterson said.