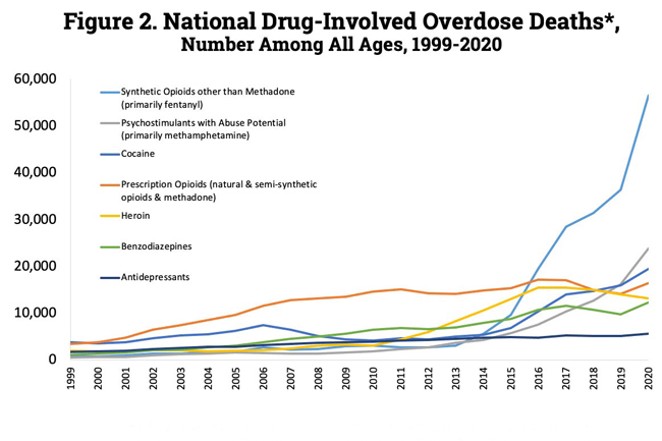

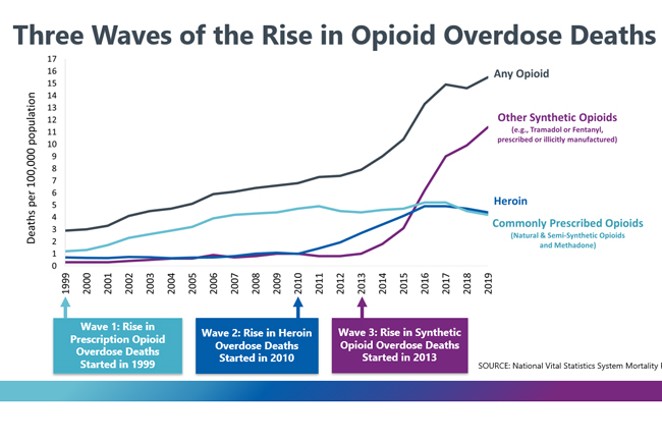

Overdose deaths exceeded 100,000 for the first time in United States history in 2021, driven largely by an estimated 71,238 deaths from fentanyl, a synthetic opioid that is 100 times more potent than morphine. Opioid overdoses accounted for 25 deaths per 100,000 people in 2021, up 15% from the year before and several times higher than the rate of 2.9 measured in 1999, when the Centers for Disease Control says the first wave of the opioid crisis began.

That first wave was pharmaceutical. About one in five Americans experience chronic pain, leading to a push in the late 1990s and 2000s to treat it using semisynthetic opioids like oxycodone and hydrocodone. In 1991, American pharmacies distributed about 76 million opioid painkillers; by 2016 it was around 289 million. As doctors doled out more doses, patients got used to it. In 2002, one in six patients took pills more powerful than morphine, and by 2012 it was one in three.

Recognizing the growing number of patients forming substance abuse disorders, health care regulators started issuing stricter guidelines on prescribing opiates, and between 2012 and 2017, first-time prescriptions fell by 54%. This led to the second wave, when fewer prescriptions corresponded to an uptick in heroin overdose deaths starting in 2010 – from a death rate of one per 100,000 people to about five. A 2016 study found that four of five heroin users had migrated from prescription pain medication.

"The first five years of my career as a counselor, I basically watched exactly that," said Josh Lair, community outreach coordinator at Ideal Option, a medical provider specializing in addiction treatments. "Their story pretty much starts with prescription pills, and then they get cut off by their doctor. They start buying them on the streets, it's way too expensive, they get introduced to heroin because it's cheaper, and then they are heroin addicts."

It wasn't long before synthetic opioids like fentanyl surfaced on the market, leading to the third surge and cementing overdose as one of the leading causes of death in the United States, claiming more lives than car crashes and firearms combined in 2021. Oregon's overdose death rate is the twelfth lowest in the country, and the state has been able to avoid the more acute epidemics of addiction seen in Appalachia, New England, and the Rust Belt. But it is trending in a dangerous direction. Oregon overdose deaths jumped from 462 to 656 between 2020 and 2021, a 28% increase. In 2019, the last year county-level overdose data are available, nine people died of opioid overdoses in Deschutes, Crook, and Jefferson Counties.

"Typically, we are lower than state averages in Central Oregon, but we're following state trends. So, we are seeing a downtrend in certain indicators around prescribed overdoses, or overdoses with prescribed opiates, and an increase of those around fentanyl," said Katie Plumb, public health director of Crook County and Chair of Central Oregon Overdose Crisis Response Taskforce.

The Unique Danger of Fentanyl

Fentanyl differs from prescription opioids and heroin in its strength, needing just three milligrams to make a dose fatal, compared to 30 milligrams for heroin. In Central Oregon, fentanyl mostly takes the form of mass-produced counterfeit pills that resemble oxycodone, but sometimes mimic other opiates, and even benzodiazepines like Xanax.

"The tablets are so well made that even experienced users say that they can't tell the difference between a counterfeit pill and a pill manufactured by a pharmaceutical company," said Sgt. Kent van der Kamp, a member of the Central Oregon Drug Enforcement Team. "To be clear, these are not pharmaceutical-grade painkillers; they are 'basement' pills made by the drug cartels. There is no quality control. Pills in the same batch can have wildly varying levels of fentanyl."

Besides pills, fentanyl can also take the form of powder that can be snorted or mixed with other drugs. Van der Kamp said fentanyl is usually sourced from Chinese-produced chemicals that are processed into pills by criminal drug networks in Mexico, who then traffic the drugs up the I-5 corridor.

It's not clearly understood why fentanyl is mostly sold as pills, but van der Kamp said it could be a way to market to people seeking prescription drugs, because pills are less stigmatized than street drugs. Also, the bright colors and various sizes could better attract teenagers. Despite fentanyl's prevalence, local officials report the drug is not popular, even among its users.

"Anecdotally people are not necessarily seeking out fentanyl for use," said Plumb. "I think it's still scary to people because of its potency and unpredictability."

Heroin is often laced with fentanyl to augment its strength. It has also been found in stimulants like methamphetamines and cocaine.

"Folks are reporting overdosing, but they swear they've never used an opiate. They solely say that they use methamphetamine, and yet they'll overdose and be revived by Narcan (a nasal spray that reverses overdoses)," Plumb said. "And so that is telling us that fentanyl is being cut into these other drugs, unknowingly to folks. And even in the instance of heroin, I think what our law enforcement is reporting in what they're seeing is that more often there is fentanyl, either in heroin, or in place of heroin." (Cont. on page 17)

In some other regions, the situation is different. A study of 308 opioid users in Baltimore, Boston, and Providence, Rhode Island, found that 27% of users preferred opioids containing fentanyl. Though some local addiction specialists haven't encountered a large market for fentanyl use, others have seen people intentionally seeking out the drug.

"I'm seeing an uptick in the fentanyl market, of people who are just seeking fentanyl," Lair said. "For one, it's cheaper, and two, the high is way more extraordinary than just heroin. The problem is that the high is not as long, so it's having individuals seek the drug more often than heroin."

“You want property crimes to go down? Have people engaged in treatment. You want people to not have their children taken from them and put into the foster care system? Help them, encourage them to engage in treatment, that’s how things start to change.”—Josh Lair

tweet this

Treatment and Harm Reduction

The extreme potency of fentanyl leads to more severe overdoses. Emergency medical services in Central Oregon administered naloxone to more than 50 people in the first quarter of 2020. Naloxone —also known by the brand name Narcan — is sometimes called the Lazarus drug because it is very effective at ending life-threatening overdoses by blocking opioid receptors in the brain. As fentanyl becomes more prevalent, more doses of naloxone are required to reverse an overdose.

"As of April of 2022, it was taking almost three doses of Narcan per overdose to bring somebody back from an overdose," said Laurie Hubbard, coordinator of the harm reduction program for Deschutes County Health Services. Comparatively, in 2020, it took an average of 1.7 doses to reverse an overdose.

The harm reduction program is borne out of a 1980s practice in response to the HIV crisis. It stresses non-confrontational support, without attempting to talk anyone into treatment if they aren't amenable to it. It seeks to reduce harmful behaviors associated with drug use.

"What it does is it provides people and services to meet people who use drugs where they're at, without trying to talk them into something different. That just helps them keep themselves safer while they're using, including while they're dealing with substance use disorder," Hubbard said.

Harm reduction tactics include providing safe equipment for injecting and smoking, distributing naloxone, recording overdose data, and providing fentanyl test strips. There has been an increased need for harm reduction services in the past few years, and Hubbard said they're distributing about twice as much naloxone as they did in 2019. Local data is imprecise, and is better at identifying trends rather than counting the specific number of overdoses.

"We do know that the majority of overdoses go unreported, so we don't necessarily get calls, because people don't engage with [the health care system], whether it's EMS or the hospital. Because you have to be using an illicit drug to overdose, that creates a dynamic where it's challenging to get help or to call for help, even in a life-threatening situation," Plumb said.

Opioids are highly addictive, and people often rely on treatment if they're looking to kick a substance use disorder, to both alleviate withdrawal symptoms and to wean themselves off traditional opioids. In Deschutes County, Ideal Option partnered with the Sheriff's Office to distribute referrals to people using opioids. The program has only been active for a couple of months, and Ideal Option couldn't provide the number of referrals by press time. But so far, they claim the program has shown success. The clinic prides itself in its ability to quickly support people who want to recover, rather than having them sign up and return later.

"The best description I've ever heard from an individual, when you're talking about withdrawal, is feeling like you have the worst case of the flu, and you got hit by a by a moving vehicle at the same time," Lair said. "The broad overview of treatment for opioids is, we need quicker access to services for individuals."

One recurring theme among people involved in substance abuse treatment is the need to destigmatize discussions about drug use, as it keeps people who may seek treatment underground.

"You want property crimes to go down? Have people engaged in treatment. You want people to not have their children taken from them and put into the foster care system? Help them, encourage them to engage in treatment, that's how things start to change," Lair said.