Lucinda Torrez was 11 years old when her older sister, Lisa Pearl Briseno, went missing in 1997. Like countless Indigenous women across the country, her body was never found.

"We have no closure at all for her," said Torrez. Her family held a service for Briseno, despite not having her body, and the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs, of which she was a member, now considers her deceased.

Growing up on the Warm Springs Reservation, Briseno acted as a role model for Torrez, encouraging her to work hard in school and strive to go to college. Briseno herself was a star student at Madras High School and went on to attend college and later intern in Washington, D.C.

When she went missing at age 28 while living in Portland, her whole family was devastated, according to Torrez. "She was loved by everybody," she said.

Few details are available about Briseno's case, which fell under state, not tribal jurisdiction. She was last seen in Portland on Aug. 27, 1997, when she left with her boyfriend in a white 1983 BMW. The vehicle was later recovered and the boyfriend was fine, but Briseno was never heard from again.

Torrez said her sister's boyfriend wouldn't do a lie detector test during the investigation, but this has yet to be confirmed by the Portland Police Bureau, which didn't respond to our requests for the police report on Briseno's case by press time.

"I think the police could have done a lot better job," Torrez said. "I think it was just kind of like, 'She's missing, she's gone, on to the next case,' like she's just a number."

For decades, Indigenous activists have been fighting to give voice to these numbers, and draw attention to the growing crisis of missing and murdered Indigenous people, which has reached epidemic levels for women and girls. In many tribal communities, women face murder rates more than 10 times the national average, according to the U.S. Department of Justice.

Additionally, a 2016 National Institute of Justice report showed 84.3% of Native women and 81.6% of Native men experience violence in their lifetime, compared to 71% of white women and 64% of white men. These crimes are overwhelmingly committed by individuals from outside Indigenous communities, the report showed.

Advocates come up against a myriad of barriers, including lack of resources, gaps in data, challenges surrounding jurisdictions and a lack of coordination between different levels of law enforcement.

In response to the growing cries for help, in 2019, the Department of Justice launched a national Missing and Murdered Indigenous Persons initiative. Officials in 11 states—including Oregon—were directed to enhance investigations into these missing and murdered person cases, develop protocols for law enforcement and improve data collection and analysis.

Cedar Wilkie Gillette, an Indigenous woman herself, joined the Oregon U.S. Attorney's Office as an MMIP coordinator in June 2020.

"This issue impacts everywhere in Indian Country," said Gillette. "It's a systemic problem."

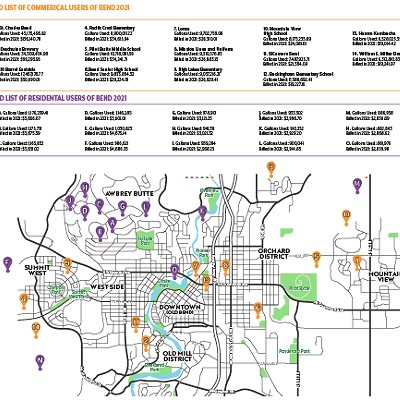

In mid February, Oregon's U.S. Attorney's Office released its first annual Missing and Murdered Indigenous Persons report, which provided a snapshot of available data. An initial analysis showed that in Oregon there are 11 missing and eight murdered Indigenous persons, four of whom are connected to Warm Springs.

Briseno is the only Warm Springs tribal member who is still missing. Fifty-eight-year-old Tina Vel Spino was missing for several months before her remains were discovered on the Warm Springs reservation this February. Another tribal member, Jonathan Thomas Gilbert, was murdered on Sept. 5, 2020, and tribal police said they had a person of interest soon after. Gunnar Bailey was also shot to death on March 17, 2019, and the FBI offered a $10,000 reward for information.

All of the Warm Springs cases are still open, according to tribal and federal investigators, though no more information is available.

An undercount

The U.S. Attorney's Office anticipates that the Oregon numbers—11 missing and eight murdered—are an undercount. There is no central database for these cases, so data was collected from NamUs, the federal NCIC database and a 2020 Oregon State Police Report, which state legislators commissioned in 2019 in order to study how to increase criminal justice resources for missing and murdered Indigenous women.According to Gillette, MMIP cases are underreported due to a number of factors. For one, Oregon tribal members who go missing outside of the state are typically not included in Oregon numbers. Tribal members are also often racially misclassified as white or Hispanic, throwing the data off.

Gillette had hoped to get more data directly from tribes for the recently released MMIP report, though these efforts were dampened by COVID restrictions. She plans to consult directly with each of Oregon's nine tribes this year.

"Reservations are small communities," she said. "They know who's missing or murdered."

Even though tribal members often know who's missing or murdered, the cases often fall outside of the jurisdiction of tribal police. According to Warm Springs Police Chief Bill Elliot, tribal members often move between jurisdictions during pow wow circuits, the annual gatherings of Indigenous people. If someone goes missing during the circuit, the case can go unreported for some time, and communication is often lacking between police in different jurisdictions.

Elliot added, "Tribal systems are not integrated in the federal or state systems."

In Briseno's case, since she went missing in Portland, the case was investigated by Portland Police, and Warm Springs tribal police never formally opened a case. Josh Capehart, lieutenant of investigations for Warm Springs Police, said that a few years ago, Portland Police did collaborate with Warm Springs to collect DNA from Briseno's family members in an attempt to identify her body, but she was still never found.

Warm Springs falls under federal jurisdiction, so investigators with the tribal police are also sanctioned as a part of the FBI Task Force and the state police. According to Capehart, this removes some of the barriers that may accompany reservations that fall under state jurisdiction instead.

But, challenges still remain in investigating these cases. Non-tribal members who commit a crime on a reservation cannot be arrested by tribal police or charged in tribal courts. According to Carina Miller, a leader in the Warm Springs community, "That in itself opens up the door for non-tribal offenders to come and harm our women." Reservations are often targeted by human and drug traffickers, who take advantage of the jurisdictional gray area.

In the U.S. Attorney's Office, Gillette is working to combat this by increasing collaboration across all levels of law enforcement. Oregon is one of six states in a pilot program focused on making tribal community response plans for when members go missing or are murdered. This plan will solidify measures for community outreach, law enforcement response, victim services and public relations and media communication.

Gillette is working with the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs specifically to create this plan, which will be incorporated into a final MMIP guide on the national level. She said the goal is to come up with "realistic solutions that would fit with the tribe."

Elliot, the Warm Springs police chief, said this includes more aggressive investigations of open cases, "so the cases don't just go cold." He said that MMIP cases did frequently "go cold" in the past when turned over to the FBI, who are often strapped by limited resources, but there is now more collaboration between federal and tribal police.

"If it's a tribal member, we'll always look into it no matter the jurisdiction in order to bring some resolution for the family," Elliot said.

As a part of a 2021 Action Plan, Gillette plans to also consult with Oregon's eight other tribal governments to make community response plans and create a working group to share all MMIP information in one place.

"I think that these conversations are happening but not all together," she said.

Grassroots action

Gillette emphasized that her position only exists because of the efforts of grassroot Indigenous activists, who pushed state and federal governments to address the long-neglected cases of missing and murdered Indigenous persons, specifically women.One of these grassroots leaders is Deborah Maytubee Shipman, a member of the Chickasaw Nation of Oklahoma and a longtime Oregon resident. Six years ago, she founded Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women USA after two of her friends were murdered near the Navajo Nation. She has since dedicated her organization to bringing missing Indigenous people home and helping the families of those murdered through the grief process.

Shipman said this problem has failed to be recognized in the U.S. for so long because Indigenous people have been "silenced" in mainstream narratives.

"Looking at us would cause people to have to look at the systematic violence that's been perpetrated on us since colonization," she said.

According to Shipman, until recently, Indigenous people were thrown a lot of "crumbs" to address the systemic problem of MMIW. But she said seeing Indigenous women band together to fight for change gives her hope, and she sees potential for the Biden Administration to address these issues through Operation Lady Justice, a federal task force initially created under President Donald Trump.

In the last few years, Shipman has seen public awareness of missing and murdered Indigenous people rise through the Department of Justice's Initiative, along with congressional action. In 2019, the U.S. Congress passed Savanna's Act to boost communication and data sharing between tribal and other law enforcement agencies in cases involving missing and murdered Indigenous women. The bill was named after Savanna LaFontaine-Greywind, a 22-year-old Indigenous woman who was killed in North Dakota in 2017 and had her unborn baby cut out of her.

Back in Oregon, Torrez, Briseno's sister, said that there is a lot more awareness about this issue than when her sister went missing in 1997, but like with Savanna's Act, it took a tragedy to get here.

"You almost have to go through something in order to get awareness," Torrez said. "There's more resources now, but at the same time, it's still happening."

She continued, "It's great that more resources are here, but are they going to work?"

Miller of Warm Springs said more focus should be put on combating systemic inequities and preventing Indigenous people from going missing or being murdered in the first place, rather than just responding to these cases once they happen.

"I think the real changes that we need to see are those essential resources getting into our communities to support these individuals before we're on that list of missing and murdered Indigenous women," Miller said, listing a need for greater mental health care, counseling, child care and housing resources in tribal communities.

Even though raising awareness through data collection is a good first step, Miller said, "I don't think this is going to be the end-all be-all. It's only the very beginning."

Though tribes are now being offered new resources to address missing and murdered person cases, countless families still lack answers and closure, like Briseno's family here in Central Oregon.

Torrez looks back on her experience of losing her sister and encourages Indigenous families to keep pushing when their relatives go missing and not to leave it up to law enforcement alone. Her family still hopes that Briseno will one day come home after being missing for 24 years.

Fighting through tears, Torrez said, "We love her, and we miss her."