Not long ago, Bend social studies teacher Brad Horn reached out to the Source to share how he and his students had recently completed a project in which each student conducted an oral-history style interview with a community member. Some talked with those involved in Oregon's deadly summer wildfires; others interviewed locals on the topic of race in Bend.

For Horn—a first-year teacher at Realms High School and a former journalist who worked for National Public Radio and The Washington Post—the assignment was in keeping with his love for reading interviews with everyday people.

"These interviews were done as part of a series of classes we call 'Power and Privilege' here at Realms High School, a public magnet school," Horn told the Source. "Last fall, given current events, race felt like the most relevant slice of the issue we could explore. Race is a topic that can make us want to shout and preach, which can lead to anger and guilt and make us shut down and stop learning. But a personal story and a human connection can be an antidote. It's a person, not a statistic. And they're telling their story, not lecturing you. It's a credit to the participants who gave up some of their time and were willing to be vulnerable with our students. As for the students, I just couldn't be more proud and impressed with what they did and what they learned not just with their heads, but with their hearts."

With Black History Month now in full swing, the work of Horn and his students offers us—and our readers—an opportunity to hear perspectives we might not have heard before, from people who live, work and play in this community.

The interviews have been lightly edited for clarity.

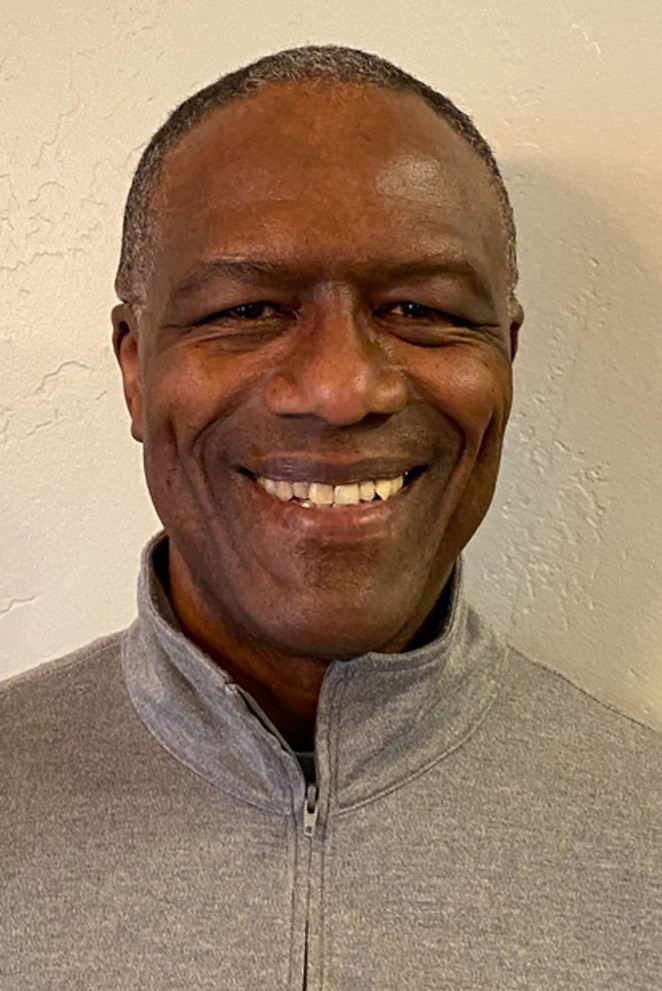

Malaku Monge, interviewed by Abraham Lindberg

Abraham Lindberg: Can you tell me a little bit about yourself, like where you are from, where you moved from and when you moved to Bend.

Malaku Monge: I am African American and Puerto Rican. I was born in Eugene, Oregon, raised there till I was 12. I moved to Miami when I was 12 and then moved to Bend when I was 13.

AL: How have you experienced race in Bend, and how can you help others understand what you have been through so we can better ourselves?

MM: I haven't experienced too much racism towards me in my time in Bend. I don't think that you can really understand it unless you have been through it—it has happened to you or you are a minority. White folks are not going to have people yell at them or call them the N word because they are white and have privilege. I don't think you can really understand how Black people feel when they get treated like that.

AL: Especially in Bend—Bend is like a bubble. I feel a little nervous about talking about race because I grew up thinking it was rude to even mention that a person was of a certain race. Do you feel that way too—and why or why shouldn't people feel this way about talking about race?

MM: I did feel that way for a while, but now that I'm growing up, I don't feel that way anymore. I think that racism is never going to be a comfortable conversation or subject to talk about, so I think the best thing to do is talk about it. Have that conversation and admit that you don't know that much about it. Be ready to hear the honest answers that you are going to hear from the person talking to you.

AL: How have other places you lived differed regarding racism?

MM: Miami wasn't a racist place—it was mostly Black, so there were not so many white people there. There wasn't too much discrimination, unless it was the police arresting a Black kid for nothing. In Eugene—I was a little kid when I lived there—I didn't understand what racism was. I wasn't worried about it so I couldn't tell you, to be honest. Overall, Bend had the most racism.

AL: Do you think that the people in Bend can't fix racism because they don't understand it or notice it?

MM: Yeah, I think it takes a lot of willingness to change something this big—but there is so much privilege that white folks have that they don't want to change it.

Andrew Johnson, interviewed by Noah Bell

Noah Bell: So, people say Bend is quote "racist with a smile." Do you agree with that?Andrew Johnson: Racist with a smile?

NB: Like, nobody's really blatantly racist here.

AJ: I would say that, in my experience growing up here, that my home is not a racist place with a smile. My experience has been overwhelmingly positive, with quite a few negatives, but I don't think that's indicative of the population in my mind. I like to hope that there's enough good people in this town that don't think that way—but there are an undercurrent of people that I have experienced who think that way and who have made it pretty blatant.

NB: So you have had bad experience with racism in Bend?

AJ: Yeah, I know my skin is light, but I'm half Black. When I was growing up, Bend was a little more than half the size it is now. So as early as when I was a baby, I don't remember this, but, my parents had me as a freshman in high school, and my dad was one of the only Black people in town. So as early as when I was a baby, a person threw a cup of ice on me and called my mom an N lover. And as recently as two-ish months ago I had a gentleman overhear me talking to someone at a grocery store about my ethnicity and called me the N word. There has been some instances in high school and middle school where the kids know, because I don't hide that about me. And it obviously isn't something I should hide.

NB: I want to hear your opinion on when people fly the Confederate flag on their trucks.

AJ: That's another thing, right? Because my experience has been one way, and normally the kids at school who were flying the Confederate flag were the ones that were saying things. I think it invokes a strong sense of dread—and a strong sense of ideals in people that I think we need to keep in mind.

I've had examples where people hang out with me where I'm like, "Oh, the Black friend."

tweet this

Maxwell Friedman, interviewed by Leo Johnson

Maxwell Friedman: Well, being dominantly white, being ethnically homogenous... it's been really weird to figure out where I align with, what culture I align with... I guess it's kind of 'cause I disconnect culturally where I don't know where to align myself. As a jazz musician, as an MC, as someone who makes hip hop, I align with my culture that way. I align with my culture through advocating for civil rights and being the vice president of the nonprofit Central Oregon Black Leaders Assembly, COBLA. So that aspect, I connect with my culture, but it being very white, it's affected me because I don't know if I should align with how I've been raised or I feel like maybe I missed out on an aspect of my culture because I feel almost guilty to be... that I have this privilege that a lot of other people (of color) don't have—like being a person of color who lives in the suburbs, with two white parents who have been incredibly supportive. But, I still... a lot of the issues that come with Bend being predominantly white, like people not really fully empathizing what it's like to be a person of color in this small community, and how some actions of people in this community discourage members of the Black community in this town from being more active in the Bend community and feeling comfortable, that's the main thing.

LJ: What are some examples of how you've been treated differently just because of the color of your skin?

MF: Well... I've had people use me as like... like...

LJ: Like the "black friend"?

MF: Like a token, yeah. I've had examples where people hang out with me where I'm like, "Oh, the Black friend," but with a lot of my close friends it's not like that. I have had people make jokes, like, pointing out, like, "Oh, you're Black." I've had some other experiences though, like walking downtown and Northwest Crossing I get looked at a lot, I get stared down a lot. I haven't had any interactions with police in this town because I'm incredibly careful not to have any interactions with police.

LJ: That's actually another question I wanted to ask. Because of you being raised by white parents, did they teach you, like, how a lot of other people of color, their parents teach them, "Respect cops—you don't want to get on the bad side of the cops." Did your parents teach you that, too?

MF: Yeah... It really got brought up when I started driving, because I've always, I've been taught you can't do whatever you want, obviously, my parents are looking out for my safety and they had to teach me that.

Yeah, I was scared, like, "Oh, I gotta drive," like, I'm terrified... I've reached out to other people of color to talk about experiences... I feel disconnected and whatnot. But yeah, I've never really had a formal talk, like, "Because you look different you've gotta be careful." It's always been more of a subtle thing. Growing up I've noticed that, and my parents know it's an issue, so I've kinda come to the conclusion almost on my own, and listening to other Black people's experiences with police, how to act. And I've had people point out or make insensitive jokes about, like, "Oh, you can't do this because you Black," or like, "You'll get shot."

I've made those jokes, too, I've made those edgy jokes like, "Oh, I can't do that," you know? "I could get shot for doing that," because I've known about police violence for a while and I know how to act. And that's why I'm working with COBLA. Anybody in a position of power needs to be held accountable for preventing racism, for perpetuating white supremacy and overall hatred in our country.

Rasia Pouncie, interviewed by Malaku Monge

Malaku Monge: Can you introduce yourself?Rasia Pouncie: My name is Rasia Mykonos Pouncie.

MM: Where are you from?

RP: Boston, Massachusetts.

MM: Cool, were you born and raised there?

RP: I was born there and stayed there till I was 9.

MM: Cool, what has your experience of racism been like growing up?

RP: It's been overt, covert; it's been very physical at times. I've had people throw us out of a cab because we were Black. I've had—that was a white man. I've had Latinos throw bottles at me 'cause I was Black. I've been denied treatment by white doctors because I was Black. I've been looked at as dirty by friends when I was in middle school because I was Black. Lots of discrimination.

MM: Wow, I'm sorry. Where have you lived?

RP: I've lived in Boston, I've lived all over Florida—so the greater Miami area as well as Fort Lauderdale, West Palm Beach. I've lived in Oregon, in Eugene, Oregon; Bend, Oregon. I've lived in California.

MM: Why did you move to Bend?

RP: For a clean, quiet place to live and good schools for my children.

MM: Compared to the—well, I won't say all of the places, but compared to the places you've lived the most to Bend, which place have you experienced the most racism?

RP: That's a good question. I mean I've definitely experienced racism in Bend and Eugene—it was more covert, so nothing outright like microaggressions and things like that, but, I would have to say the most racism I've experienced is, was in larger cities. But I wouldn't say it's because of the fact that it's a larger city. I would say it's just because I spent more time there, and it would be Miami, Fort Lauderdale.

MM: I know sometimes people feel scared or nervous to talk about the subject of racism. What would you say to them to make them feel more comfortable?

RP: I would say that the best way—it's never gonna be a comfortable conversation. The best way to approach it is just to have the conversation, to admit that maybe you don't how to talk about it, but to be open to learn and be open to communicate and ask the questions that maybe you don't feel like you should be asking and be open to the honesty response that you get.

MM: How do you think your own race has impacted your life? And what difference has it made?

RP: It's made me resilient. It's made me a fighter. It's made me aware of things that other races don't have to be aware of, unfortunately. It's given me so much spiritual enrichment, as well as historical and ancestral enrichment, so it's fed me in many beautiful ways.

As I got older, more rebellious, it was always the same thing. Stay in your place. And so that's how I survived, I think, because I always had good manners and always basically stayed in my place.

tweet this

George Lee, interviewed by Llyr Clembury

Llyr Clembury: So you haven't experienced racism in Bend—what about in Maryland where you grew up?George Lee: Yes, in Maryland where I grew up. Basically, Maryland was the northernmost state that had seceded to the South. So growing up in Maryland, it was separated by Black schools. There was a white high school 2 miles from where I lived, but I was bused 20 miles away to go to school. And it was blatant discrimination there. There was a definite color line; wealth and poverty was—you know, the whites had the wealth, in the Black side, the property. My grandfather was a sharecropper. Do you know what a sharecropper is?

LC: No.

GC: Well basically it was a system where the white land owners owned land and the Black people had to work the crops and what it was, since the white people owned the land, the Black people worked the tobacco farms and they shared the profits from the crop. And basically it was one of those situations where *inaudible*. Yeah, there was quite a bit of discrimination where I grew up in Maryland.

LC: how did you deal with that, or did you? Or did you just have to live with it.

GL: My father/grandfather, they taught us how to survive. And the thing was, be very polite— 'yes sir, or no ma'am.' You couldn't call the white people by their first name—it was always Mr. So-and-so or Miss So-and-so or Miss/Mrs. Whereas the white people would just refer to us as by first name. They would call us a number of names or whatever and it was—always a ranking order and so my father made us be subservient, basically. It was always, 'know your place,' 'you can't go there,' and it was never talk back, just be good little boys and girls. That's how I survived it.

As I got older, more rebellious, it was always the same thing. Stay in your place. And so that's how I survived, I think, because I always had good manners and always basically stayed in my place. So that's how I survived.