To start, teachers will wear masks, students will stay 6 feet apart and no more sharing crayons or geometry tools. Some kids might stay with one group of students throughout the day in the same area of the school building. Others may come in on alternating days with their cohort.

The Oregon Department of Education—in partnership with Gov. Kate Brown and the Oregon Health Authority—released a 47-page book of guidelines for the 2020-2021 school year last week, helping schools create their own “blueprint” for reopening. The plans will need to be passed by Bend-La Pine Schools board, then reviewed by Deschutes County Health Services and finally sent to ODE.

All schools must present a plan that will facilitate physical distancing classrooms, as well as consistent sanitization of high-touch surfaces and enforcement of handwashing practices.

We are very interested in getting all students who want to be in schools back in,” she said. “For families that have a medical reason or feelings of concern during the age of COVID before a vaccine, we are really fortune to have an online program. -Lora Nordquist, Bend-La Pine Schools interim superintendent

tweet this

When planning class sizes, each person—including teachers and aids—must have 35 square feet of space. Students will no longer pass through school hallways en masse between classes; instead, teachers will move.

Lora Nordquist, BLPS’ interim superintendent, said the biggest challenge for will be the physical distancing and space requirement.

“We are very interested in getting all students who want to be in schools back in,” she said. “For families that have a medical reason or feelings of discomfort about returning in the age of COVID before a vaccine, we are really fortunate to have an online program.”

Going online

BLPS has offered an online program for K-12 students since 2006, originally created for students with scheduling conflicts (like budding athletes), but it also helped those that got behind in classes or needed advanced classes that weren’t offered at the right time. During the 2018-2019 school year, the program served more than 4,000 students, with 700 who received the bulk of their instruction online only.

What happened this spring due was not a matter of simply moving whole schools onto this online program. Teachers retained their pre-COVID responsibilities and met with students in virtual classrooms. They created video lessons and delivered assignments through a sometimes confusing array of online platforms.

“We learned a lot of lessons this spring,” Nordquist said. “We have decided to be on one consistent platform; Google Classroom for elementary and Canvas for six through 12. If we have to close for several days at some point, the plan is that teachers, parents and students will already know how to make it work.”

Canvas is the leading online platform for colleges in the U.S., surpassing Blackboard in 2018, according to Inside Higher Ed, a digital media company for higher education.

We know we play an important childcare function, for both parents in the community and also our own staff. - Lora Nordquist

tweet this

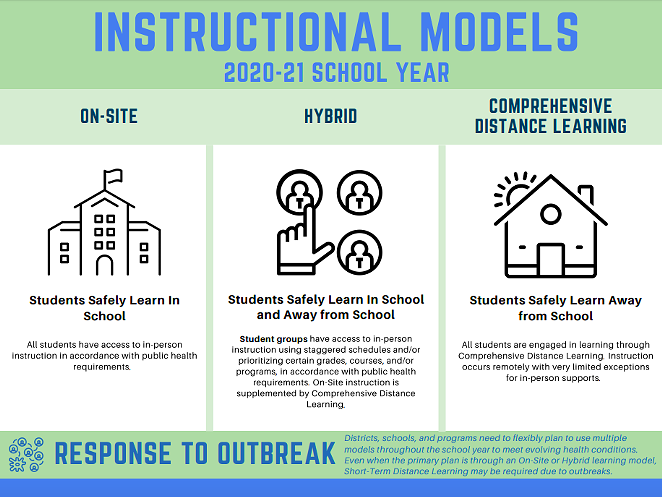

Scheduling for physical distance

This fall, schools in Oregon can choose from three models: in-person classes, all online or a hybrid of both. The state’s guidelines promote synchronistic teaching models whenever possible. This means in a hybrid classroom, a half the students could be in class, while the other half watch the classroom activities from home and then the groups switch the next day. But everyone is learning the same material at the same time.

But the opportunities for asynchronistic learning—or participating in class activities at different times then other students—may be one of the bright sides of adjusting to life during the pandemic, Nordquist said.

“This spring many teachers made videos of individual lessons,” she said. “Now a student who might be too shy to ask a question in class, they can access that video [and learn at their own pace]. Also teachers might provide a variety of assignment options online to increase engagement. This is something that could be great all the time.”

Playing by the rules

The state requires rigorous sanitation protocols: everything from desks to library books must get wiped down. But students don’t have to wear masks: The guidelines state in bold that students without masks “must be provided access to instruction.” No mask shaming in Oregon schools.

All staff who come into contact with students will have to wear masks, including bus drivers and the people who work in the kitchen. In some cases, office staff might set up plastic barriers at their desks or just wear large, clear face shields throughout the day.

Everyone entering the school building will be screened for the typical COVID-19 symptoms and those that do show any signs of illness will be isolated and then sent home. In order to come back to school, anyone sent home will have to get tested for COVID-19 or wait three days after their fever breaks regardless even if they test negative. If anyone does test positive, they’ll have to wait a minimum of 10 days before returning or after testing negative twice.

The ODE included a number of recommendations for schools to promote culturally responsive and anti-racist teaching, and to address “student belonging, student engagement, supportive relationships, wellbeing, and addressing racism, xenophobia, sexual harassment, and other forms of bullying and harassment.”

The plan noted that discrimination against Asians and Asian Americans has increased since the pandemic began. Schools must also check with their local tribal agencies before sending in their plan.

Rumblings of Local Dissent

Not everyone is thrilled about the state’s guidance and mandates.

Rep. Cheri Helt (R-Bend) released a statement on June 10 asserting that Oregonians have the right to an education, along with a call to make sure the new rules from the state are not “excessive and unrealistic.”

“Failure to open is unacceptable and unfair to all our kids and families. We cannot sacrifice two years of learning to fear and a lack of creativity. Local districts should be allowed to design safe classroom learning experiences,” Helt said.

Helt told the Source her primary concern is that the regulations from the state are a one-size-fits-all solution which could make education impossible to deliver at a local level, especially in the face of budget cuts. She expressed frustration with the requirement that every person needs 35 feet of space: This could pose an obvious impediment in older schools or in classes with traditionally larger student counts.

Nordquist also took some issue with the 35-square-feet requirement, noting that given the current science around distancing, it seems somewhat arbitrary. Particularly in BLPS, even an extra 5 square feet per person of space could make or break some plans to provide in-classroom instruction to all students, five days a week, she said.

“We know we play an important childcare function, for both parents in the community and also our own staff; we have quite a few teachers with young children,” Nordquist said. “Part of our thinking is to try to at least get [full-time, in-person instruction] for students through sixth grade.”

Oregon is one of only three states that has a minimum legal age to leave kids home alone, and that may be the only option for some parents this fall. Oregon’s requirement is 10 years old, while Illinois is 14 and Maryland is 8 according to the federal government’s child welfare department.