In a Land Birthed by Fire

A three-part series exploring how Central Oregon can safely live with fire

A three-part series exploring how Central Oregon can safely live with fire

In Central Oregon, the reality of living with fire, and its offspring smoke, is unavoidable. But, unlike other natural disasters that regularly devastate communities worldwide, we have some measure of control over fire.

Over the next few months, the Source Weekly will investigate how prepared we are for the next wildfire – from how the forests are being managed to how to accommodate the region's rapidly growing population without increasing wildfire risk. Because, as the experts stress, it is not a case of "if" but "when" a blaze will be in our backyard.

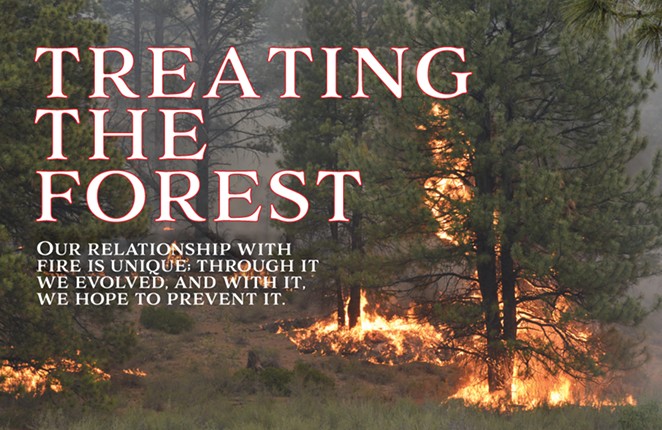

Part One: Treating the Forest

It's a little after 9 am on a crystal blue day in Bend. After many false starts, spring has arrived and brought with her warming air and light breezes. Flowers are blooming, bees are buzzing. The landscape is lush, and on the outskirts of the Deschutes National Forest – just a few hundred yards from Cascade Lakes Scenic Byway — a firefighter lights a drip-torch and sets fire to the ground. This is a test fire ahead of a 209-acre prescribed burn. A final check that today, after years of preparation and work, this land can be burned.

Conditions on this day in mid-May are indeed good: vegetation is deemed dry enough to burn but not too dry that it'll move fast and far; the trees are holding on to enough moisture to ensure they too won't go up in flames, much of the land has been thinned, mowed and masticated. Smoke forecasters have checked their models and predict that incoming breezes will lift the fire's smoke up and (mostly) away from communities along the Deschutes River.

According to the U.S. Forest Service, 99.84% of prescribed burns go as planned. But when they go wrong, they can go very wrong. The most recent prominent example is the 2022 prescribed burn in the Santa Fe National Forest that left its boundaries and merged with another out-of-control prescribed burn, eventually resulting in the largest wildfire in New Mexico's recorded history. Or, for a more local example, a controlled burn that same year in the Malheur National Forest in eastern Oregon burned roughly 20 acres of private land and resulted in the Grant County Sheriff arresting the fire's burn boss on charges of reckless burning.

Against this backdrop, the stakes today are high. But according to many experts, the risk of not burning is higher. Two years ago, in a national first, the federal government released a wildfire crisis report, "Confronting the Wildfire Crisis: A Strategy for Protecting Communities and Improving Resilience in America's Forests," identifying key areas across the country where communities were at the most risk for devastating fires. Among the first 10 landscapes identified and chosen to receive funding and begin implementing the Wildfire Crisis Strategy was Central Oregon. The initial investment was $131 million.

“We have proven successes of stopping wildfires based on these treatments.” —Jaimie Olle

tweet this

And, the threat to the region increases daily as vegetation in surrounding forests grows, drought dries out the land and more people move to town, fueling development and pushing farther into wild lands. The burn in west Bend today is part of a pilot project resulting from the wildfire crisis report. It allows for burning more aggressively, closer to communities than before and with support across governmental agencies, from the local to national level.

A History of Suppression

Fire in the Cascade Mountain range forests that surround Central Oregon is not new. It was here long before European settlers and was used by Indigenous tribes as a way to help maintain forest health. Much of the knowledge around exactly how and why tribes burned in the area has been lost, but there is enough physical evidence remaining and early accounts recorded by settlers, to know that the use of fire was intentional and sophisticated, according to a USDA report from 2003 entitled, "References on the American Indian use of Fire in Ecosystems."

"Generally, the American Indians burned parts of the ecosystems in which they lived to promote a diversity of habitats, especially increasing the 'edge effect,' which gave the Indians greater security and stability to their lives," the report reads. "Their use of fire was different from white settlers who burned to create greater uniformity in ecosystems."

Historically, the fires that moved through a forest like the Deschutes National Forest – either by natural elements or intentionally set – were low-intensity fires, the kind a prescribed burn done today is meant to mimic. The pattern of fire was cyclical, occurring every five to 25 years, according to specialists. Until the early 1900s.

Following a series of catastrophic wildfires in the early 1900s the federal government committed to minimizing the threat of wildfires to citizens by suppressing nearly all fires. In 1933, the Tillamook fire burned nearly 300,000 acres, making it the largest wildfire at that time in the Northwest. In its wake, the Forest Service instituted a "10 a.m." policy – meaning it would seek to extinguish any fire by the following morning.

These suppression efforts were shockingly effective – working 95 – 98% of the time. But once suppressed, the grasses, shrubs and young trees grew, resulting in fuel accumulations that all but ensured that the next fire would be even worse. And at the same time, logging in other parts of the forest stripped the land of the largest and oldest trees – further weakening the forest to fire.

Reintroducing Flames

It's nearly noon at the west Bend prescribed burn near Cascade Lakes Byway and across the landscape low fire burns away at shrubs and overgrown grass. Models show that the work done today will help protect communities downhill if, or when, an unplanned blaze ignites. As we enter the burn zone the light around us darkens, taking on a dusk-like appearance. Smoke lingers in the trees, making it hard to see, bright shoots of orange and red dot the distance. With a steady pace a firefighter walks across the landscape dripping flames in a line and occasionally stopping to survey the work, creating a mosaic of burned land.

Trucks and other emergency vehicles are on standby to support burn efforts and mitigate the risk of fire getting out of hand. It's calm and quiet, except for the sound of crackling vegetation.

"It feels pretty awesome," says Jaimie Olle, public affairs specialist for Deschutes National Forest, as she walks along the burn area. "It is awesome to do good work," she adds, "work where we're protecting our communities."

Olle is animated when she talks about the work the Forest Service is undertaking to undo the suppression policies of the past and the growing risks associated with climate change and drought. This year the Deschutes National Forest plan is for around 10,000 acres of burning, a substantial increase from the average over the last 15 years of 4,500 acres. To support these efforts, the federal government has allocated nearly $18.2 million this year for wildfire prevention in Central Oregon. It's an ambitious undertaking, but one that experts from a range of disciplines agree is needed to protect communities like those in Deschutes County from a wildfire racing through town.

In recent years, as Olle points out, there have been examples of fire charging toward homes only to meet an area that was previously burned. "We have proven successes of stopping wildfires based on these treatments," she said.

The most recent example she gave was the Rosland Road Fire in 2020. The fire, just a few miles east of La Pine and the Newberry Estates subdivision, was heading toward homes when it hit an area that had been treated with the removal of overgrown vegetation, small trees and a prescribed burn. Upon entering the treated area, the fire dropped out of the tree canopy and onto the ground where firefighters were able to engage with it.

"We have many stories like that in Central Oregon that have really shown that this work does work, and does help protect communities," Olle said.

Smoky Outlooks

This first-in-the-nation pilot project in west Bend is also a test case for how a range of agencies can work in collaboration to protect exposed communities, not just from fire but from the effects of hazardous smoke produced during a prescribed burn, and in larger quantities during a wildfire event.

"It's a pretty profound thing that our community was selected to be the first in the country, the first community," said Sarah Worthington, regional climate and health coordinator for Crook, Deschutes and Jefferson County. "All these agencies are eyes on us, they really want to understand how all of these partners can work together." And, she adds, "There is no playbook on how to do this work." They are writing it as they go.

Worthington's role includes getting out messaging to Bend residents and surrounding communities that a prescribed burn is happening (to this end, there is a text service and website for up-to-date information) and educating the public on how to best prepare for smoke and wildfire season. "We're doing everything we can to protect health while also providing as much resources as possible to be able to support a larger scale burn than what we're accustomed to. To increase that pace and scale because west Bend in particular is right on the WUI [wildland urban interface]."

Smoke is a rapidly increasing public health concern in Deschutes County and in much of the U.S. as the size and number of conflagrations across the continent grows. According to the wildfire crisis report, smoke from wildfires now causes around 25% of all harmful exposure to fine particulate matter (a form of air pollution) in the United States. A recent Oregon Department of Environmental Quality report on wildfire smoke found that eastern Oregon has experienced a 24.2-fold increase in days impacted per year with Air Quality Index values at or above unhealthy for sensitive groups. That's the highest increase in the state. Long-term smoke impacts on people, and especially children and the elderly, can range from increased risk of asthma attacks to exacerbating pre-existing conditions and even a greater risk of heart attacks and sudden death.If we don't do it kind of on our terms, Mother Nature will do it on her terms, and that is really scary.” —Amber Ortega

tweet this

During the course of this project, Worthington said a small study is happening simultaneously to gather data on how indoor air quality is impacted by prescribed burns and wildfire smoke events. The project, a joint effort by Deschutes County Public Health Services, Oregon Institute of Technology and Deschutes Collaborative Forest Project, includes placing 65 monitors in volunteers' homes around the area to see how indoor air in different types of homes and locations is impacted when the air outside turns smoky.

Mitigating smoke exposure to a community begins before a prescribed burn is lit – first by smoke forecasters determining optimal times to burn and second by public health services working to inform the public that smoke may impact air quality and how best to prepare.

Though it may not seem like it when a thick dark plume is rising up from the forest, a lot of consideration goes into how much smoke drops into where people live. Amber Ortega, a regional smoke coordinator and air resource advisor for the Forest Service, is one of the experts helping forecasters determine when smoke from a controlled burn will have less of an impact on the region. Smoke forecasting is a newer field of study but one she has been doing for nearly two decades.

As a specialist in smoke, Oretga understands well the risk of exposure for people and appreciates the seriousness of balancing smoke now versus smoke – or worse, fire later.

"Do we consent to the risk of a little bit of smoke for a night or so in order to create kind of a fuel break so that if wildfire is running into town, there's a place where firefighters can anchor and slow it down and scare that fire away from town?" she said. "Or do we as a community prefer, like, no smoke, and, you know, we'll take our chances."

“You need to be able to put more smoke into this city” —Phil Chang

tweet this

For County Commissioner Phil Chang, who sits on the Deschutes Collaborative Forest Project and is a liaison for the Deschutes County Public Health Advisory Board, the choice is easy.

"We have had some really significant house-destroying events in Deschutes County, particularly back in the 1990s," Chang said, referencing the Awbrey Hall fire in 1990 that destroyed over a dozen homes in a matter of hours. A decade ago, the Two Bulls Fire burned nearly 7,000 acres and threatened over 250 homes on the west side of Bend.

With 400,000 acres of dry forest in Deschutes National Forest alone identified as needing active restoration, Chang said these burns are necessary, and allowing for higher AQI readings during prescribed burning windows must happen.

"You need to be able to put more smoke into this city," he said. "And we will mitigate the heck out of that smoke so that the impacts of it on our community are not as severe."

The Mop Up

As the crew finishes the prescribed burn for the day, they make final laps around the 209-acre site, checking for any areas that are too hot to be left to burn. Tomorrow there'll be another burn nearby — west of Bend and in the Metolius Basin north of Sisters – and another 462 acres of forest treated. This burn went according to plan, and though it wasn't thousands of acres burned, it was the kind that Jaimie Olle with DNF points to as being "really, really good acres," like those that stopped the Rosland Road Fire near La Pine, or the acres burned last year directly across from homes in Sunriver.

However, the work ahead remains daunting, and since fire is cyclical, this area will need to be treated again in the not-too-distant future. Add to that equation that the window of when it's optimal to burn is small and shrinking, and the outlooks for completing this work are not good.

If you think about it, it's like trying to push a rock uphill," said Amber Ortega, smoke coordinator. "It's like every year when that little chunk of land doesn't get fire, your hill just got bigger. And so the need to burn is increasing because the amount of forest that is overgrown, dead down and under drought is only increasing.

"We're trying to chip away each year," she added. "Just a couple more units and a couple more prescribed fires. And yet each year the amount of forest that needs to see fire just keeps growing. If we don't do it kind of on our terms, Mother Nature will do it on her terms, and that is really scary."

—This story is powered by the Lay It Out Foundation, the nonprofit with a mission of promoting deep reporting and investigative journalism in Central Oregon. Learn more and be part of this important work by visiting layitoutfoundation.org