-Part One of a three-part series on the dam removal and restoration of the Klamath River along the Oregon-California border.

Millions of pounds of algae-filled sediment. Thousands of fish. Thousands of homes, no longer powered by hydro. Dozens of deer. A handful of residential wells.

For some, these are the casualties of the largest dam removal project in history.

For others, they are the unfortunate but expected mishaps along a path to restoring an entire river basin, once the third-most productive salmon-bearing river on the West Coast. And even while those casualties make headlines, the seeds of hope are literally beginning to sprout on the Klamath River.

Advocating for a watershed

With a moniker like "the largest dam removal in history," chances are you've heard something about this project. Over decades, tribal members from the Yurok, Karuk, Hoopa, Shasta, Klamath and other tribes have engaged in advocacy for the Klamath, considered one of the most ecologically important watersheds in the U.S. They've brought to light the dangers of allowing warm, putrid waters to sit stagnant behind the hydroelectric dams, which have provided power for the area but don't offer flood control nor irrigation. In addition, the tribes have advocated against over-irrigation of the basin, which has destroyed thousands of acres of wetlands and imperiled water quality in the Upper Klamath.

Eventually, the tribes and their partners prevailed upon PacifiCorp, the owner of the four dams now in the process of removal, to recognize that removing the dams would be the less-expensive option for resolving this conflict. Signatories that include tribes, various nonprofits and the states of California and Oregon created the Klamath River Renewal Corporation, the entity whose sole job is to remove the four dams that blocked fish passage on the river. That process is now well underway, and it's a project that's simply staggering in scale.

Reservoir drawdown

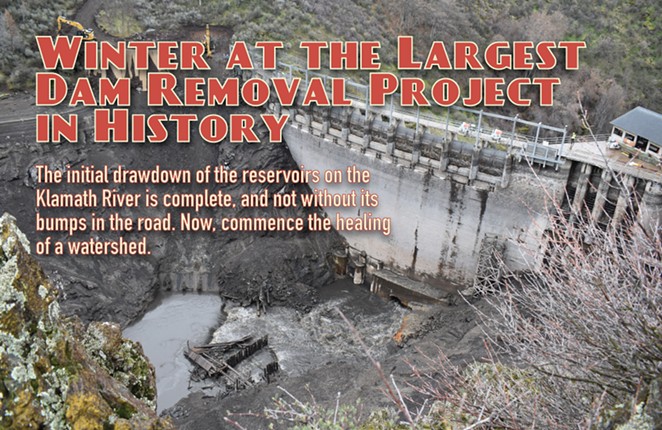

I arrived at Iron Gate Dam, among the three remaining dams slated to be removed in 2024, on Feb. 15, the day the KRRC announced that the initial phase of "drawdown" of the reservoirs behind Iron Gate, Copco One and JC Boyle dams was complete.

Upriver was a muddy but drying former lakebed. Downriver, a river currently filled with sediment and smatterings of dead fish along the banks.

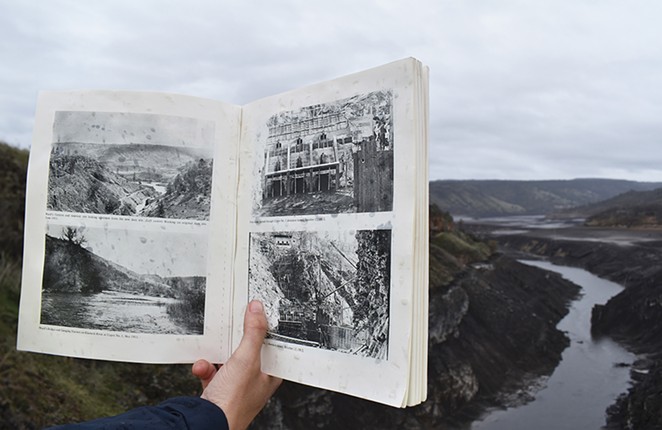

Walking along the top of Iron Gate was literally like taking a walk with history. In just a few short months, no one will be able to take in the view from this man-made height. Iron Gate, like the other dams, will be taken apart in pieces so as to have the least impact on the health of the river. The pieces will be carted off to fill the hole that was created when crews built Iron Gate in the 1960s.

The drawdown process, which began in January, involved finding the safest ways to let millions of gallons of water — and about 5 million cubic yards of sediment, accumulated over decades — flow downstream. At Copco Dam, which sits between the former Copco 2, removed in 2023, and Iron Gate, that involved carving out a giant hole at the bottom of the dam. Engineers feared that the existing headgates on the dam and the adjacent slope was too unstable to allow that much water and sediment to flow through, so creating a new hole was the solution, said Ren Brownell, public information officer for the KRCC.

"Draining the reservoirs is a critical step on the path to deconstructing the remaining three Klamath River dams that are slated for removal later this year," the KRCC explained in a Feb. 15 press release. "With the reservoirs emptied, the Klamath River now winds its way through the former reservoir footprints, cutting though a century of accumulated sediment and finding its historical path. Extensive testing of the sediment that had accumulated behind the dams revealed that it is predominantly dead algae and is not a concern for human health."

The KRRC chose this time of year to drain the reservoirs because adult salmon are still out at sea, and the juvenile salmon that remain tend to spend the winter in tributaries and not the main stem of the Klamath. To preserve any coho in the main stem, the Karuk Tribe fisheries department captured some 250 coho salmon and relocated them to rearing ponds for the duration of the drawdown process.

"An environmental disaster"

Depending on who you ask, the Klamath River is an "environmental disaster" due to the toxic algae that's accumulated behind the dams for decades — or, it's an "environmental disaster" due to the presently turbid waters and the masses of non-native fish that have died in the days since the reservoirs began to drain. People have stocked catfish, perch and other fish in the man-made lakes in recent decades, and seeing them die from suffocation in the turbid waters has evoked plenty of emotion among nearby residents, KRCC's Brownell told me.

Below Iron Gate Dam — long the last stop for salmonids aiming to spawn along the Klamath River — is where I saw introduced fish species lying dead. This type of fish die-off was expected by the KRRC and its partners in this stage of the project.

"Our native fish have evolved to survive many challenges, including periods when water quality is not ideal," said Daniel Chase, director of Fisheries, Aquatics & Design for Resource Environmental Solutions, the contractor handling restoration. "High levels of suspended sediment in the river is not unusual in itself. Burn scars, mudslides and other events can contribute a great deal of sediment to the river and cause fish mortality, but the vast majority of fish respond by moving into tributaries or finding areas with better water quality. In this they can find ways to survive conditions and persist even when conditions look bad to us."

During the fall run of Chinook salmon along the Klamath, "we're going to see something very different than what we've seen before," said Ann Willis, California regional director for the nonprofit American Rivers, who's been involved in the project since 2008. "The patterns of flow in the river will move away from reservoir release to dynamic and a more natural flow pattern – and that's huge."

In the days following initial drawdown of the reservoirs, several groups of deer got stuck in the mud and were either euthanized by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, or died — though crews quickly created deterrents along the river to avoid more wildlife getting stuck in the mud. Wildlife officials also euthanized wildlife before the drawdown, after finding them suffering from the effects of drinking water containing toxic cyanobacteria.

And while the efforts now are aimed at restoring water quality, the water quality in the Klamath is "currently poor," stated a press release from KRRC, with the impacts of dam removal on water quality expected to taper off over the next two years.

Adding to the strain for some local residents, several residential wells adjacent to the former reservoirs have dried up post-drawdown, Brownell of KRRC said. Funds from the KRRC and a mitigation fund are aimed at helping adjacent homeowners source drinking water during the drawdown process and eventually site new wells, Brownell said.

Replanting

This winter, the story of the Klamath dam removal project is one of getting dirty before you can get clean. But mere hours after initial drawdown began, crews from local tribes began the work they've long waited to see commence: replanting the former reservoirs and banks with native species. This is the years-long effort that will ultimately result in a restored watershed.

Tribal members gathered native seeds around area watersheds for years to use in the restoration work. On my visit, dozens of tribal crew members were dotted around the former bottoms of the Iron Gate Reservoir, planting seeds and starts in the rain. Alder and cottonwood trees gathered along the river corridor by the Yurok and Shasta people will also be planted along the 2,200 acres of reservoir beds now exposed after drawdown.

"We contracted with the Yurok Tribe to perform the initial revegetation work, and they literally could not wait to begin," said Dave Coffman, Klamath Restoration Program manager for Resource Environmental Solutions, the restoration contractor. "Crews were planting acorns and broadcasting seed by hand the day after the first reservoir started to drain. We have billions of seeds in storage so the disturbed areas can be fully treated."

By spring, crews hope the newly planted vegetation will help slow erosion during the heavy river flows of the warmer months.

The future of the watershed

Initial drawdown is one of many steps along the way to restoration. After the last three dams are removed this spring, many will await the joyous return of salmon above Iron Gate Dam. The states of Oregon and California and their respective departments of fish and wildlife are working through the details of who gets the land revealed by the former reservoirs, as well as the lands used by PacifiCorp for power transmission and maintenance.

On the California side, the Shasta Indian Nation has requested return of the lands they historically stewarded, among them the Ward's Canyon stretch of the Klamath, but officials there have yet to announce who will ultimately steward the lands.

On the Oregon side, Philip Milburn, Klamath and Malheur Watershed district manager for the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, is playing the long game. The lands will remain in private hands through the duration of the restoration, which Milburn expects to span about five years.

"We're working with our partners to develop a vision for those lands," Milburn told the Source Weekly. That involves a "visioning process" facilitated by the Rivers, Trails and Conservation Assistance Program, a part of the National Park Service.

"The National Park Service will collaborate across multiple states and jurisdictions including the states of California and Oregon, multiple Tribes, BLM CA and OR, and several recreation, conservation and community stakeholder groups to identify and document their vision for a free-flowing Klamath River post dam removal, to make recommendations on potential future opportunities to protect and conserve the river and cultural heritage, while providing access and education," reads a statement on the NPS site.

But movement on any re-allocation of lands will come after the river has a chance to re-establish itself, Milburn said.

And whatever happens, it's land that will be able to be enjoyed by all. As part of the agreement that formed the KRRC, the lands revealed by dam removal must be used exclusively for habitat, recreation and education.

"It fills my heart to know that salmon will migrate through this river reach on their way to spawn in the upper basin," said Yurok Vice Chairman Frankie Myers in a September press release. "For the last century, we have watched the dams suffocate the life out of the river and it has negatively impacted every member of our tribe."

—Stay tuned for parts two and three, covering restoration and returning recreation in the Klamath River, in the summer and fall.